Book Review

I remember reading Dylan Thomas’ famous poem “Do not go gentle into that good night” and my teacher asking whether we would rather our loved ones “go gentle” or “rage, rage.” The question has stuck with me, and I could not help but be reminded of it as I read Bill King’s poetry.

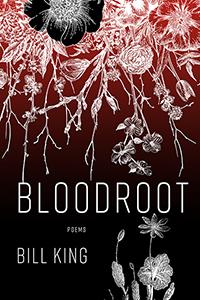

Bloodroot is Bill King’s first full collection, published posthumously.*

It is a book of place, set among the Blue Ridge and Appalachian Mountains—a narrative of experiences within Appalachia. King’s speaker wanders about his beloved wooded patches, vegetable gardens, and stripped mined mountains like a ghost, praising and protesting nature’s life cycles, questioning where he fits into them. King reminds us in his poem “Even the Wild Iris” that “there is a price / for flight,” whether the “price” be growing up, mountaintop removal, or even our own transience.

Much of King’s collection revolves around the speaker’s awareness of his mortality. In the poem “This World Should Be Enough” the title itself hints that a single life is indeed not enough, especially one shortened by illness. Within the poem the speaker has one of his many out-of-body experiences, even switching from first to third person: “I rise / above a man with everything to lose: / he’s looking downriver at a thin thread / lit like a slow-burning fuse.” The nature loving “grown boy” at the beginning of the book remembers his childhood, then protests the destruction of his beloved outdoor sanctuary, and finally confronts life’s final question: what happens next?

The standout poem from Bloodroot is King’s multi-genre piece “How to Destroy a Mountain.” King skillfully juxtaposes an educational lesson plan titled “Cookie Monster’s Delight: Grades 3-5” with “a collection of oral history interviews about mountaintop removal…in Appalachia.” These two pieces, the lesson plan and the interview, act as two voices in conversation.

This work is no gimmick. “How to Destroy a Mountain” deserves to be anthologized widely as it presents readers a clear picture of mining’s effects on communities. King takes risks with this three page poem,

and they pay off.

“Give each student a toothpick to mine their deposits. / Hear that quiet? / Have them just mine

ONE cookie first. / You know they’re about to set off a shot / when they shut down the machines. /

Make a pile of chocolate chips and one pile of the cookie crumbs. / I used to look up at the mountains. / Count coal deposits and record… / But now I look down on them.”

Seth Grindstaff teaches in Northeast Tennessee where he lives with his sun-loving wife and four children. His work has appeared in journals such as Appalachian Places, The Baltimore Review, Blue Earth Review, and James Dickey Review.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________