Trampoline

A Novel in five acts by

Robert Gipe

≈

Author's Statement: I was born in North Carolina in 1963 and was raised in Kingsport, Tennessee, a child of the Tennessee Eastman Company, Pals Sudden Service, and the voice of the Vols, John Ward. My dad was a warehouse supervisor and my mom a registered nurse. I went to college at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina where I was a DJ for a student radio station I helped start. I went to graduate school at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and got a masters in American Studies. I worked as a pickle packer, a forklift driver, and eventually landed a job as marketing and educational services director for Appalshop in Whitesburg, Kentucky in 1989. At Appalshop I worked with public schoolteachers on arts and education projects. I met my wife, Robin Lambert, at a conference in 1992, and we bonded over an interest in rural communities and an opposition to school consolidation. We married in 1993. She is my heart's delight. Since 1997, I have been the director of the Appalachian Program at Southeast Kentucky Community & Technical College in Cumberland, Kentucky. I am one of the producers of Higher Ground, a series of community musical dramas based on oral histories and grounded in discussion of local issues. I am also a faculty coordinator of the Crawdad student arts series. I have had fiction published in Appalachian Heritage and have attended the Appalachian Writers Workshop in Hindman every year since 2006.

I have been working on the characters in Trampoline since 2006. The narrator is Dawn Jewell. She lives in a coalfield county in eastern Kentucky, and is in high school when Escape Velocity takes place. She's having a rough go of it. The sound of people telling one another stories is the most precious sound in the world. Trying to catch that sound on the page is my favorite part of writing. Most of my favorite writing—Flannery O'Connor's stories, the novels of Richard Price and Charles Portis—seems to me written by ear. When writing is going best for me, it's like taking dictation from voices I hear in my head. As far as the drawings go, I have drawn pictures all my life, much longer than I have written stories, and with more compulsion. Escape Velocity is the first time I have seriously tried to integrate fiction and drawing. I love episodic storytelling, especially the great HBO series—The Wire, Six Feet Under, Deadwood, etc.—and have enjoyed thinking about how to break a story into semi-coherent pieces.

—Robert Gipe

≈

Escape Velocity

Part One: Driving Lesson

Mamaw stared through the gray-gold woodsmoke curling from a pile of burning brush in the front yard. I set a glass of chocolate milk at her elbow and sat down next to her on the porch glider.

“That’s where they’re going to strip,” she said, nodding at the crest of Blue Bear Mountain. “They’ll start mining on the Drop Creek side. But they’ll be on this side before you graduate.” She sipped her chocolate milk. “You watch.”

Mamaw linked her lean arm through mine and told me about growing up on Blue Bear Mountain. Her stories smelled of sassafras and rang with gunfire, and the sound of her voice was warm as railroad gravel in the summer sun, but the stories flitted through my mind and never lit. I was fifteen.

That August, Mamaw signed her name to a piece of paper, a lands unsuitable for mining petition the state calls it. The petition stopped a coal company from strip mining on Blue Bear Mountain. The coal companies told everybody Mamaw’s petition would be the end of coal mining. Halloween, Mamaw got her radio antenna broken off her car. We never even had a trick-or-treater.

Mamaw didn’t get her antenna fixed until the Saturday before Thanksgiving. That afternoon Mamaw came in my room. I was eating M&Ms straight out of a pound bag, about to make myself sick. They weren’t normal M&M’s. They were the color of the characters in a cartoon movie that hadn’t done any good and the bags ended up at Big Lots, large and cheap and just this side of safe to eat.

“Put them down if you want to go driving,” Mamaw said.

I took off running for the carport. I was strapped into Mamaw’s Escort a long time before Mamaw came out. She got in the car and turned to me, the keys closed in her hand.

“Put your seatbelt on,” she said.

“It is on Mamaw.”

“You know you got to keep your eyes moving when you’re driving.”

“Yes, Mamaw.”

A pickup truck covered in Bondo pulled up and spit out Momma.

“Going for a driving lesson?” Momma’s cigarette bounced in her mouth.

Neither one of us said anything. Momma jumped in the back seat. I closed my eyes and wished her gone. She was still there in the rearview when I opened my eyes. I started the Escort and backed onto the ridge road.

“Slow down now,” Mamaw said. “You aint in no hurry.”

My cousin Curtis come flying the other way on his four-wheeler. Mamaw’s Escort side-swiped the wall of rock on the high side of the road. The sound of the scraping metal felt like my own hide tearing off.

“Daggone,” Momma said. “You’re worser than me.”

“Hush, Patricia,” Mamaw said. “Dawn, are you all right?”

“Yeah,” I said, my hands shaking.

“Get on home, then,” Mamaw said.

When I pulled into the carport and shut off the motor, Mamaw and Momma got out and looked at the side of the car.

“Whoo-eee,” Momma said.

They went in the house, left me sitting there breathing hard, all flustered. I turned on the radio. It was tuned to a station Mamaw liked. Most of the time they played old country music, but that night they had some kind of rock show on. “I’m about to have a nervous breakdown,” a boy sang. “My head really hurts.” The guitars sounded like power tools being run too hard. I’d never heard such before. I turned it up til the speakers buzzed. The next song was a country song, all slow and twangy. I was about to turn it off when the singer sang “my head really hurts.” The country song had the same words as the one before. At the end of the song, there was the sound of a throat clearing. The voice that spoke sounded like spent brake pads.

“That was Whiskeytown doing the Black Flag song ‘Nervous Breakdown.’ Before that we had the Black Flag original. You’re listening to Bilson Mountain Community Radio. I’m Willett Bilson. This here next one is another record I got from my brother Kenny, by the band Mission of Burma.”

Willett Bilson sounded about my age. He sounded like someone I would like to talk to. The power tool guitars started again. Willett played five angry, reckless songs in a row. My head got light. I started the engine and slipped the shift into reverse. The bands came on one right after another, rough and mad, and they carried me through curve after curve. It felt good, like riding a truck inner tube down a snowy hill curled up in my dad’s lap. When I pulled into Mamaw’s, rain pecked the carport roof, bending the last of the mint beside the patio. Inside, Momma was gone, and Mamaw set a bowl of vegetable soup in front of me. She didn’t say anything about me taking the car back out.

The next day after school, Mamaw asked me if I wanted to ride with her to Drop Creek, the place where she grew up, to look at a man’s house. I ran out of the house and started the Escort.

“You aint ready to drive to Drop Creek,” she said. You need more practice.”

“Well then, I aint going.”

“Yes you are. Scoot over.”

The house we went to had vinyl siding and set on block. The yard was neat and the gravel thick on the driveway. A little boy with a head like a toasted marshmallow bounced a pink rubber ball against the wall under the carport. When he saw us he hollered in the house. A stout silver-haired man came out.

“How yall doing?” he said. He told me how tall I was getting like everybody does. “Want a piece of pound cake?” People always fix pound cake when Mamaw comes to talk about their troubles with the coal company. We went inside. It was quiet and neat in there too.

“Look at that Christmas cactus,” Mamaw said. “So beautiful.”

“Thank you,” the man’s wife said. “It likes that spot.”

The wife had a northern accent. She moved through the room making things straight. Mamaw and the silver-haired man set down at a table in the kitchen next to the wall. I stood at Mamaw’s shoulder. The man showed Mamaw pictures he pulled from a drugstore one-hour photo folder.

“These was done before they started blasting.” The man pointed at a picture of the block at the base of the house. “I took these the other day.” He showed Mamaw a picture of a crack running up through the same block. Then he showed her a closeup picture with a thumb stuck up in the crack.

Mamaw said, “Did the state inspect?”

“Yeah,” the man said, “they did.”

“What did they say?”

“I keep notebooks where I write down when the blasts happen and how long they last. They looked at them said they’d look into it.”

“That all they said?”

The man’s wife set down a plate of sliced pound cake, a bowl of strawberries, and a tub of Cool Whip. Mamaw looked at the pound cake, then she looked into the man’s eyes.

“They said subsidence was natural, could have caused those cracks,” the man said.

“Oh bullshit,” Mamaw said. “When was this house built?” Mamaw put a piece of pound cake on a paper napkin, took a big bite out of it.

“Daddy built it with Granddaddy. Right after him and Mommy got married. Finished it a year before they went to Michigan. So, 1958, 1959. Something like that.”

“And you aint never had no cracks before, have you?”

“No ma’am,” the man said. “Not that I know of.”

“Pure sorry,” Mamaw said, spooning out strawberries and Cool Whip into a bowl. She crumbled the rest of her pound cake down on top of the strawberries and Cool Whip and mashed it all up with a spoon. Then Mamaw said, “What do you want to do about it Duane?”

“Well,” the man said, “I hate to see people get run over.”

“You coming to the meeting Tuesday?”

“Yeah,” he said, “I got a doctor’s appointment in Corbin. But I should be back.”

“Well,” Mamaw said, “we could use you. You coming tonight to the planning meeting?”

“I’ll be there,” Duane said.

I went outside. Marshmallow boy threw his ball into a pile of leaves. A little black dog leapt in the leaves and disappeared. The rustling leaves looked like Bugs Bunny moving underground.

Mamaw and the boy’s daddy come outside and the man showed Mamaw the cracks.

“The blast shook the whole house, throwed her china plates out on the floor,” the man said. “They was stood up in a

cabinet and they busted all over the place.” The man shook his head.Mamaw toed a weed in the gravel. The little dog ran up to me and the boy, dropped the ball and backed off, its tail

wagging. Mamaw told the man to thank his wife for the pound cake, that it was real good. Mamaw drove us back to

Long Ridge.The state scheduled a meeting the Tuesday before Thanksgiving for people to come and give their testimony about

whether or not the company’s permit to mine should be approved. Monday night Mamaw’s group had a meeting in town at

the library to talk about what they were going to say at the meeting on Tuesday. That’s the way it was that fall.

Meetings about meetings, and then a meeting on top of that. Again, she made me go, and again she wouldn’t let me

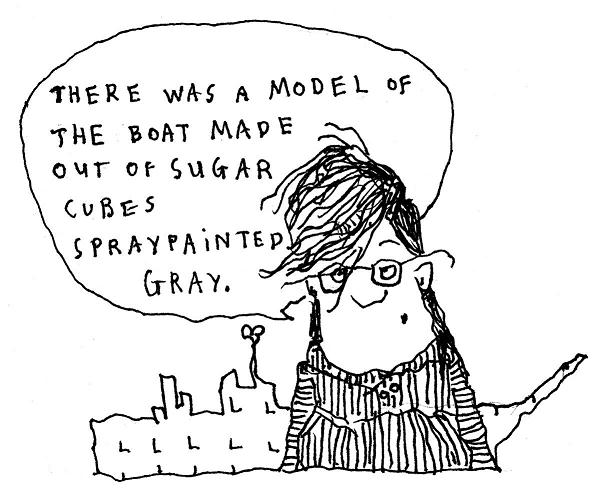

drive.I sat at the back of the room in the basement of the public library and looked at pictures of the USS Canard County

in a glass case. It was a navy ship that hauled tanks and trucks to Haiti and the Persian Gulf and Argentina til

the Navy sold it to Spain.

The organizers that the statewide group sent came in carrying rolled-up maps and armloads of flyers and information sheets. The one named April wore a homemade sweater of purple yarn that hung big on her. The one named Garrett had leather patches across the shoulders of his sweater, like he was on a submarine. They both had big wild hair. Mamaw said they looked like woolyboogers.

April and Garrett talked awhile and then different ones in the group said things. A man with a receding hairline stood up and said that they would use the same explosives on that strip job that blew up the building in Oklahoma City. A woman with short hair and a sticky-faced little boy said they used to eat fish out of the creek.

“You see what it is now,” the woman said. “Yellow mud.” She put spit on her thumb and used it to wipe her boy’s face.

Mamaw said, “Duane, why don’t you say what happened to yall.”

Duane told what had happened to him, to his house.

April told them they had to practice what they were going to say, have their facts straight, if their petition was to stop any new strip mines on Blue Bear Mountain. They had to have goals, April said. She put paper on the glass case that held the sugar cube battleship and made people make a list of goals. Garrett put big maps on the case and showed them what lands would be protected.

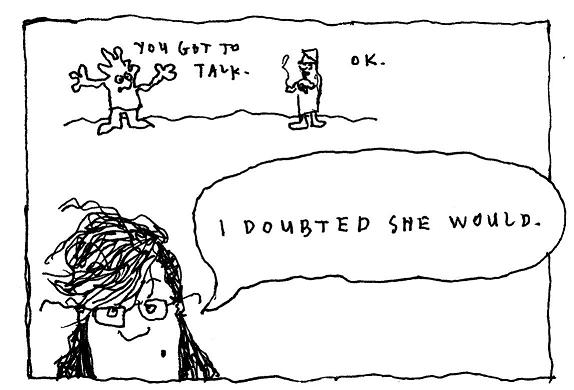

When they took a break, a woman with a gray ponytail and trembling hands out smoking said the dust from the coal trucks was so bad she couldn’t let her grandbabies play outside. April tried to get her to say she would talk at the meeting.

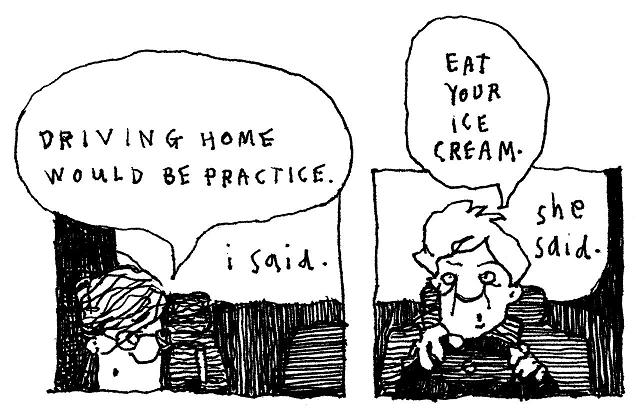

On the way home, Mamaw stopped at the Kolonel Krispy dairy bar and got a double fudge shake with brownies swirled up in it. We sat in the parking lot and watched the redlight and Mamaw said all strip mining ought to be outlawed. I asked her if I could drive home. She said I needed to practice more.

When we got home, Mamaw looked at a pile of mail on the kitchen counter. “Where’s my check?” she said. Three of Momma’s cigarettes were in the ashtray. Mamaw called my uncle Hubert’s house and asked where Momma was. They said she’d gone to Wal-Mart. When Mamaw caught up to Momma in the Wal-Mart parking lot, Mamaw’s face was solid red.

“You come here,” Mamaw said, hard as a broomstick to the back of the legs.

Momma kept walking towards the store. I guess Momma didn’t think Mamaw would do anything in the Wal-Mart parking lot.

Mamaw caught up to Momma and got her by the arm and smacked her in the face. She stuck her hand in Momma’s front pocket and pulled out a wad of money.

“You don’t do me that way,” Momma yelled.

“Watch me,” Mamaw said.

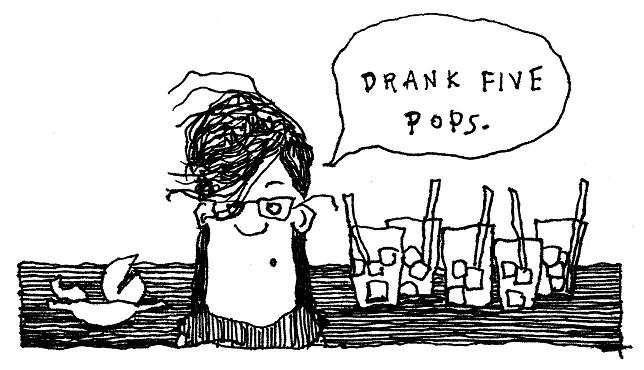

Then they both went to yelling at the same time. I went in the store, looked dead in the eye of the people coming out, the ones who didn’t know yet Cora Redding and her druggie daughter were having it out in the yellow stripes of the crossing zone. I went back to jewelry and asked my dad’s niece who worked there to take me home. She said it would be an hour. I wandered through the store, through the Christmas candy and blow-up snowmen and stupid dancing Santas playing the electric slide and stupid reindeer socks. My cousin took me to the snack bar and bought me everything I wanted to eat. Pizza sticks. Two slushies. Then we went to the Chinese restaurant. I ate every fried egg noodle they had in there.

When my cousin dropped me off at Mamaw’s, Momma and Mamaw sat at the kitchen table, hundreds of envelopes and flyers saying write the governor to protect Blue Bear on the table between them. Momma helped Mamaw stuff the envelopes like nothing had happened. I was so sick on cookies and pop and hot dogs and Chinese food.

But I didn’t. I went to my bed panting like a black dog in August and swore to the ceiling I wouldn’t never have a child. When I slept, I dreamed I was playing music on the radio with Willett the DJ.

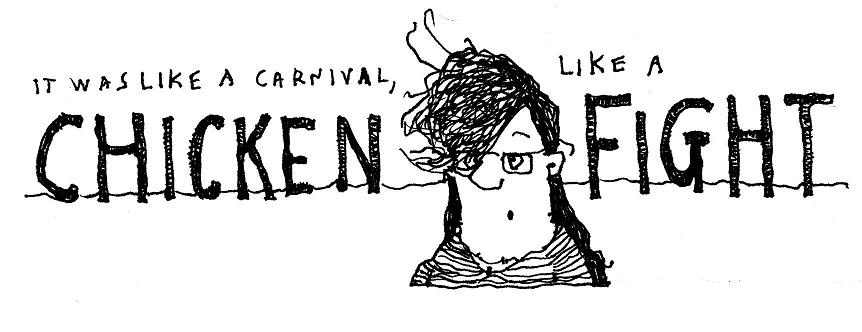

The next day in biology, a girl from up the river sat behind me and talked to her cousin the whole class about whose chicken nuggets had better crust. ‘They got too much pepper on theirs.’ ‘Them others is too mushy.’ I was ready to kill her. I turned around and said, ‘There’s more to life than chicken nuggets, you know.’ She looked at me like I wasn’t there.

I told my friend Evie about the chicken nugget girl when we were out in the parking lot drinking beer at lunchtime.

“I whipped that girl one time,” Evie said. “It wasn’t fun at all.”

I asked her why not.

“She’s too stupid,” Evie said. “It was like stomping a baby bird.”

I told Evie about the band that played the nervous breakdown song. Black Flag. She said she never heard of them. She only listened to what was new. I told Evie about the radio station on Bilson Mountain. She said only old people and hippies listened to that station.

Mamaw picked me up after school. “I need to stop by Duane’s,” Mamaw said.

The sun peeped over the ridgeline and lifted steam off Duane’s roof. In the shadows there was still frost on the yard. A dark pile of something lay in the carport. I thought it was a wadded-up shirt. It was the little black dog frozen solid. Mamaw knocked at the kitchen door and went in before anyone answered. I stood in the carport looking at the dead dog. It was going flat. Its tongue was out. There was no sign of the boy. The pink ball was up against the back wheel of Duane’s truck. Mamaw came out of the house. “Let’s go,” she said.

“What happened, Mamaw?”

“Duane aint coming to the meeting.”

“Why not?”

“Somebody fed his dog broken glass mashed up in hamburger.”

The meeting was in a stone community building the VISTAs built on Blue Bear Creek back in the 60s. There must have been two hundred people there. Where Blue Bear had the state’s highest peak on it, people all over were excited about protecting it. It wasn’t just an ordinary mountain with ordinary people living on it. It belonged to the whole state.

Three people from the state—two men and a woman—sat in front of the stage at a table. Their powder blue shirts had button-down collars and an embroidered patch of the state seal on the sleeve. Hair striped the top of one man’s head. The other had a thick bronze helmet of hair. The woman’s eyes were wide behind clear-framed glasses, cheap like they gave us for free at school. The three of them sat behind their table. They stacked and restacked their papers, took folders out of file boxes and then put them back in.

People filed in in clots of three and four. There were painted signs saying stuff like “SAVE BLUE BEAR,” and “COAL KEEPS THE LIGHTS ON” strung out along the walls of the community center. People settled in, talking low to them they came with, leaning forward and greeting the people on their side with pats on the back and handshakes, smiling.

When time came to start, the man with the bronze helmet of hair leaned forward into a microphone. “Good evening everyone. This hearing is required by law, and pertains to mine 848-1080, amendment three, a surface mining permit application in the Drop Creek and Little Drop Creek watersheds in Canard County, Kentucky. Everyone who wishes to speak should have already signed up. All speakers will be limited to three minutes. If anyone has more to say, they may wait until everyone who has signed up to speak has spoken and then we will go around again. I would remind everyone no decision will be made tonight. Everything said will go into the file and will be taken into consideration as the Cabinet makes its decision. We will begin in three minutes.”

After three minutes, they called the name of the first woman signed up to speak. The state woman brought her a wireless microphone. The first woman said she was proud of her husband, that she had married him because she wanted to be a coal miner’s wife. She said she would not be ashamed of what he did and would not allow her children to be ashamed of what he did.

The second person to speak was also a woman. She said the state should consider all the trash that was in the creeks, how terrible a shape the road was in. All the dust from the coal trucks flying up and down the road was terrible. She couldn’t even hang her clothes out on the line she said and when she said something to one of the drivers he was just rude.

The third speaker he talked about the ozone layer, how there was holes in it and how we couldn’t go on burning coal forever, that we needed to think about the future, about what we were leaving behind for our children. He talked for a while longer and the man from the state had to tell him his time was up. The speaker said he had more to say, and the state man said he could give his paper to him and he would attach it to what all else he had.

Then the man from the state said he wanted to remind everybody that they was only there to consider testimony pertaining to mine permit 848-1080 amendment three and that of course people could use their minutes anyway they wanted to but that that particular permit application was what they were there for.

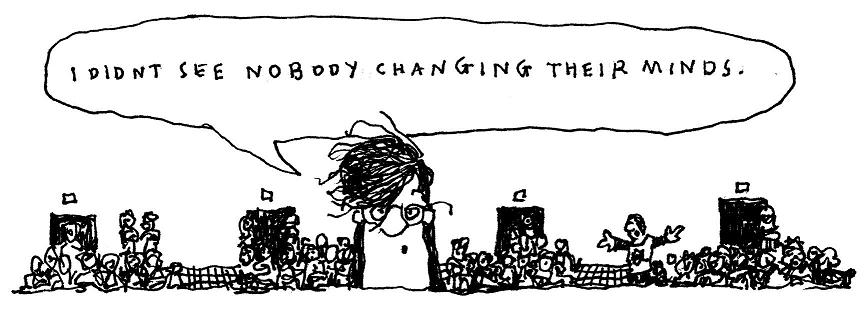

Mamaw sat stone still in her folding chair and the speeches went on and on. Every speaker tried to talk people into believing what they themselves believed.

The florescent lights flickered. Four different ones needed changing. Out the high windows, the lights of coal trucks streaked past. The state people sat like prizes at a carnival game, eye wide and blank, stuffed pink monkeys, green hippopotamuses piled too close together. Every once in a while they would take a note, but not that often.

A woman I’d seen at Mamaw’s meetings called the coal company out by name, said they’d told her mother they weren’t going to strip mine her land, that they was just going to build a coal haul road across it and that they wouldn’t be out there even a month. She said they’d promised to build a road out to her family’s cemetery—widen it. And then when her mother signed her rights away they’d stripmined the shit out of it—that’s what the woman said—and they’d mined right up to the cemetery and probably would’ve mined right through it if she—the daughter—hadn’t come back from Georgia. There wadn’t no way, that woman said, that company ought to be allowed to mine coal period, much less on Blue Bear. They ought to be put in jail that woman said, everyone of them, and especially you she said, and pointed to a man with a wirebrush moustache standing in the back spitting into a plastic pop bottle, his arms folded across his chest.

“Especially you, Mickey Mills that lived right here in this community and lied to my mother. You’re a sorry excuse for a man,” that woman said and started towards him before her husband stopped her.

Then a woman stood up and said “You aint taking my husband to jail. You’re just a busybody. You don’t live here no more and don’t deserve no say in what goes on here.”

The man from the state got on the microphone. “All right. Order. Please.”

The next speaker was a man in a sweater vest and a green plaid shirt I didn’t know. He talked about the Indiana bats and the Turks-cap lilies and other plants and animals that only lived in Kentucky near the top of Blue Bear Mountain. I didn’t know what difference that would make to anybody. Mamaw told me it did.

A thick coal company office man stood up and told how many jobs the company made, about their participation in the youth baseball leagues and their big ads in the high school gymnasium. Another company man talked about how that if they didn’t approve these permits that it would likely mean the end of coal mining in Canard County and maybe all of Kentucky. He said people didn’t know how the coal industry could fall apart at any minute and then where would Canard County be? When he asked that question he spread out his arms and turned to the crowd and it seemed to me that that was who he was talking to, anyway. He finished up by saying that state should approve the permit and get out of the company’s way and let the good working people of Canard County do what they do best—do better than anyone in America—run coal. When he said that there was all kinds of cheering and whistling as he sat down.

The next person to speak was the woman with the pulled-back hair who had been at Mamaw’s meeting, the one I’d swore would never have spoke. She was on the other side of Mamaw from me, her paper shaking in her hands. She put her other hand on the back of the folding chair in front of her, barely able to see over the frosted blond head of the miner’s wife sitting in front of her.

“My name is Agnes Therapin. I live on Little Drop Creek.” Her back straightened when she said the name of the creek. “I am against this here permit. They’s people that lives beneath these strip jobs. It aint out in a desert somewheres. It’s up the creek from me. This here is the third time you have let them add on to this strip job. I wish you’d never let them start but I don’t know why you didn’t just let them mine the whole thing to begin with. Then we wouldn’t always have been a-hoping that maybe we might have a decent place to stay.” Her hands beat restlessly on the back of the chair in front of her. The miner’s wife leaned forward, turned to look at Agnes. “My mommy lives with us,” Agnes went on. “She has a bad leg and this dynamite has knocked her out of bed more than once. We thought you fellers—you come up here from Frankfort or wherever—and I guess I thought you was there to protect us. To protect our homes and our property. I thought that was what the law was supposed to be there for. To keep the peace. Well you fellers need to know and I don’t know if you all have been up there or not but let me tell there aint no peace on Little Drop Creek.”

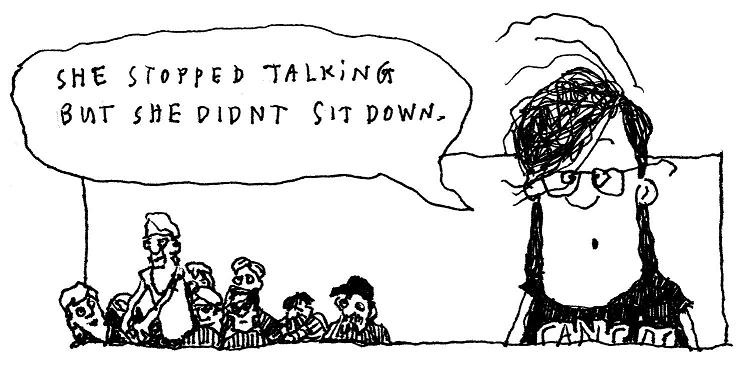

Agnes’ neck was stiff. She arched her back like it hurt.

She stared at the state people. People were quiet but the seconds passed and people started to rustle.

“Thank you, Ms. Therapin.” The state man said her name wrong.

“You are supposed to protect us,” Agnes shouted. “Surely they’s laws against blowing up people’s houses. People aint setting off dynamite at your house are they? Don’t reckon they come blowing yore people up do they? Where do you live?”

“Thank you ma’am,” the state man said.

“Where’s your house at?” The state woman came to take the microphone from Agnes. Agnes jerked it away.

“Sit down, Ms. Therapin,” the state man said.

“Maybe we ought to come set a couple shots off at your place.” Agnes’ neck was red as a beet. “See how you like it.”

“Agnes,” Mamaw said, and covered Agnes hand on the back of the chair with her own. Agnes sat down. Another woman across the room with “I heart coal” on her t-shirt stood up and faced Mamaw.

“Cora Redding, this wouldn’t be happening if you weren’t stirring everybody up. You don’t live on Drop Creek. You moved to town. You wouldn’t have no business, you wouldn’t be sitting on your little pile of money, if it wasn’t for the working people around here, people mining coal. You need to mind your own damn business.”

“Anyone who cannot remain civil,” the state man said, “will be removed from the meeting.”

The woman stuck her finger out at Mamaw. “You need to keep your big fat nose out of things don’t concern you.”

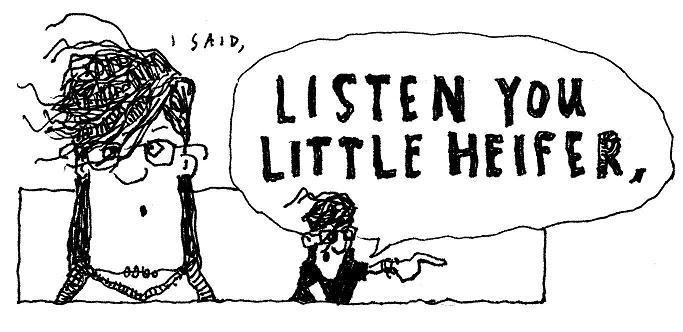

I stood up. I pointed back at the woman.

I said, “You don’t need to be telling my mamaw what her business is. You don’t know my mamaw. You aint got no right to talk to my mamaw.”

“Young lady,” the state man said, “you are speaking out of turn.”

I wasn’t done. “What do you want us to say? ‘Go ahead and tear up the world. We’ll just get out of the way while you destroy ever thing our friends ever had? Here take my house; I’ll just live in this here hole in the ground. Yeah, go ahead and set that big yellow rock on our heads. We’ll be fine.’”

“If I could ask the deputy sheriff…” the state man started.

“Dawn, sit down,” Mamaw said. “Sir, she don’t mean it…”

I sat down. A buzzing in my head kept me from hearing what was said after that. I wished I hadn’t spoken. I wished I hadn’t said a word.

Someone held up a jar of dirty water. Somebody brought in a bunch of kids carrying a banner. I’m not sure what side they were on. When it was over Mamaw had to shake me to get me to move. I dreaded walking out. I wasn’t invisible anymore.