Featured Artist

“Writer with a mountain-shaped soul”

William Woolfitt

Will Woolfitt at Plenty Downtown Bookshop, Sawmill Poetry Series, 2024: photo by Erin Hoover

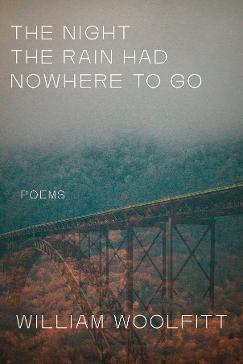

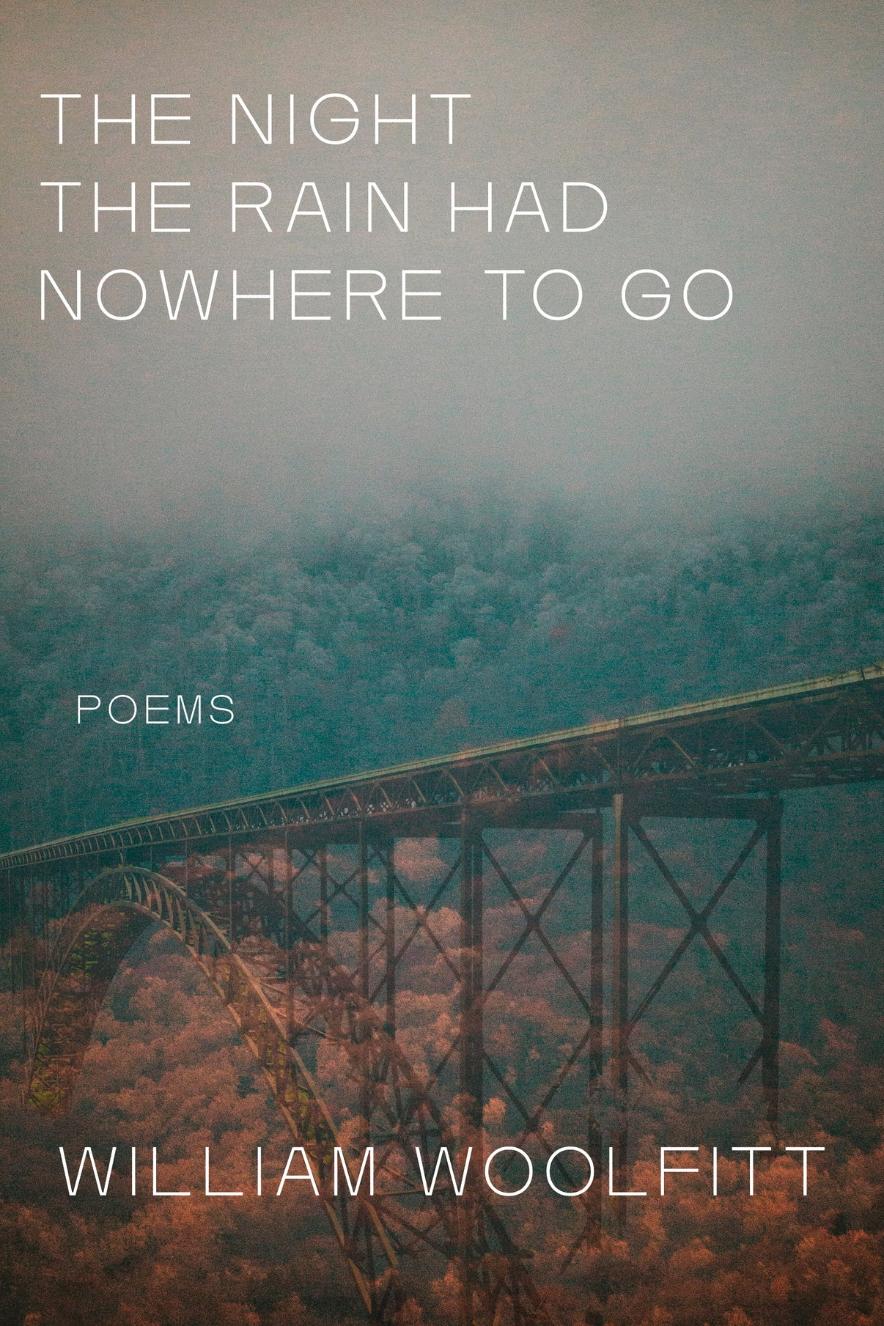

We spoke with multi-genre writer and native West Virginian William Woolfitt recently. Will is marking 2024 as the year when he published two new books. The Night the Rain Had Nowhere to Go, a much-anticipated poetry release from Belle Point Press, was released in June, 2024, and his book of essays, Eyes Moving Through the Dark is forthcoming soon from Orison Books. Of his new poetry collection, poet Joan Kwon Glass says “these poems are both elegiac and reverent, grounding in their histories and stunning in their imagery.” Will’s book of short stories, Ring of Earth, was released from Madville Publishing in 2023. (Read our review of Ring of Earth.) Additionally, Will has authored three poetry collections: Spring Up Everlasting (Mercer 2020), Charles of the Desert (Paraclete Press, 2016), and Beauty Strip (Texas Review Press, 2014). His fiction chapbook The Boy with Fire in His Mouth (2014) won the Epiphany Editions contest judged by Darin Strauss.

His writings have appeared in scores of literary magazines, including AGNI, Blackbird, Image, Tin House, The Threepenny Review, Gettysburg Review, Poetry International, African American Review, Indiana Review, Ruminate, Michigan Quarterly Review, The Missouri Review, Epoch, Spiritus, and other journals. He is the recipient of the Howard Nemerov Scholarship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and the Denny C. Plattner Award from Appalachian Review.

Will founded and edits Speaking of Marvels, a gathering of interviews with the authors of chapbooks, novellas, and books of assorted lengths. Speaking of Marvels just celebrated publishing 500 interviews with writers. Will is associate professor of English at Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee where he lives with his family.

Louise Nevelson was the daughter of Russian Jews who had fled the pogroms in Ukraine. In her forties, she walked the midnight streets of New York, Little Italy, Skid Row, gathering scrap wood from trash cans, scrap wood with nails sticking out. She said that she was giving the scraps “an ultimate life, a spiritual life that surpasses the life they were created for.” She also gathered wooden vegetable boxes and wine crates. At dawn, in her studio, she dipped all the wood she had found into troughs of black paint.Later, she would arrange the scraps in boxes and display them in art galleries. Later, she would stack the boxes full of scraps and make walls, and then installations, and monuments, and altars, and a chapel.My younger son convinces my wife and me to gather sticks and daisy-like weeds with him wherever we go—the playground, the greenway, the field beside the church. Sometimes, he ignores the sliding board, collects fallen leaves instead. He loves to work with cardboard boxes from the grocery store, dog food boxes, diaper boxes. These he crayons, and climbs in, and builds with, and tears into pieces.I want to give him my attention, be present to him, but I also want to start writing again. I try to think of a way forward. Later, while he naps, I will try to find some scrap—a detail, a sliver of memory, a chunk of text I might quote from—and to cobble from that a sentence or two. Maybe I’ll puzzle together a box of words. Later, if I have enough of these, I will try to arrange them, stack them, fit them into an essay of many small parts, a segmented essay—sort of like Louise Nevelson stacking her crates to make a wall.

Still: The Journal: Who are some writers that have influenced your own work?