Book Review

anthology, Fisher, Gray, Stevens, eds.

Thorncraft Publishing, 2024

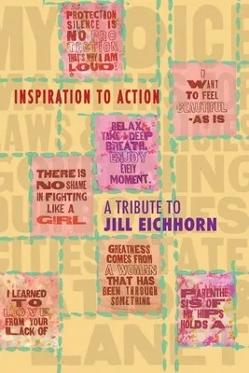

Communities need connectors. Thus, when a community loses a long-standing nexus of resources and values, it is surprising that its members do not reel apart, splintering in separate directions. Especially when an enduring influencer dies abruptly—one week after receiving a breast cancer diagnosis—we might expect the lost gravitational pull to leave those remaining weightless and adrift. Yet we are not undone. If depleted and disoriented, we are charged when an individual makes our individual potential apparent. We cannot keep telling ourselves that one vote, one voice, one gesture is of little consequence. Published this August by Thorncraft Publishing, Inspiration to Action: A Tribute to Jill Eichhorn—Professor, Activist, Peacekeeper illuminates one woman’s sphere of influence.

In her foreword, publisher Shana Thornton remembers being a student in Dr. Eichhorn’s graduate class. To describe the impact of the discussions her professor stimulated, Thornton conjures the learning hub where students could “sweep books across to one another, stack piles of notes, and dig into the challenges to our personal expressions.” She acknowledges that safe space Eichhorn protected for students to bond, to advocate for complexity, to disagree, to question, and to engage with not only the empowerment of knowledge but also the vulnerability of learning. Eichhorn honed that art, Thornton suggests, by remaining “a perpetual student.”

The volume opens with an essay by Eichhorn on pedagogy. Her teaching philosophy was undergirded by reckoning with “the traditionally patriarchal paradigm that privileges male experience over female experience.” Such injustices must be transformed, she insists, adamant that we can and must face the confrontations with ignorance, fear, and resistance that learning requires. There are countless ways to do so, she says, but the common imperative is to remain “vigilant to what is invisible or devalued.”

Other contributors describe Eichhorn’s emphasis as an educator to integrate and apply education in daily life. They list opportunities she created inside and outside the classroom to value and reveal hidden experiences, such as “The Clothesline Project.” In collaboration with other universities, Eichhorn hosted a campus space for survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault to refuse to be victimized. Side by side, t-shirts hung together in the University Center to call out abusers with painted, scrawled, and drawn messages. If inspiring, these annual reclamations of agency also challenged their makers, audience, and organizers. Anyone could see from the hundreds of shirts Eichhorn prompted, hefted, and unpacked between teaching other classes, that such projects can be uneasy or uncelebrated. Yet, they prove by accrual that one person’s initiative can change the collective.

Later in the book, we learn that Eichhorn received Austin Peay State University’s Distinguished Community Service Award. In demonstration of her spirit and the spirit of this award, she used its accompanying funds to purchase tickets for the Feminist Majority Leadership Alliance to attend an event featuring Gloria Steinem. In addition to the FMLA, Eichhorn supported many local, regional, and national organizations including the NAACP, Legal Aid of Clarksville, Sexual Assault Center, Safe House, Centerstone, the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship, and others. She was committed to helping uplift one another and worked hard to strengthen alliances.

Inspiration to Action evidences the reach of one woman who taught and mentored numerous people junior and senior to her, but it also demonstrates the synergy generated by a community. Co-edited by Beverly Fisher, Lee Gray, and Jennifer Goode Stevens, this tribute makes clear that every force field has multiple centers of gravity and orbits inside orbits of influence.

In their honor and hers, I will offer a confession Eichhorn makes posthumously through her opening essay: she was also frightened. Fear of losing her institutional status nearly prevented her from staging, with her students, decades of performances of Eve Ensler’s “The Vagina Monologues.” Later, fear of being judged or shamed nearly prevented her from participating as a cast member in the play, but she took the stage anyway. She heeded the advice of Eleanor Roosevelt “to look fear in the face…Do the thing you think you cannot do,” and she accomplished it.

In return for her courage, she learned that each production of Ensler’s play engendered healing. She wrote that to stand on stage and give voice to a part of ourselves that was once silenced, censored, reviled, and exiled enacts a “public ritual” that “frees us to fill the silence with our own sound, our embodied and empowered voices.” May we all receive such an education.

Amy Wright is an Appalachian writer from Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of Denver and has authored three poetry books, six chapbooks, and co-edited the Virginia volume of The Southern Poetry Anthology (Texas Review Press). Her nonfiction debut, Paper Concert: A Conversation in the Round, (Sarabande Books) won a Nautilus Gold Award for Lyric Prose. She has twice been awarded a Peter Taylor Fellowship to the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop. In 2022, she served as the Wayne G. Basler Chair of Excellence at East Tennessee State University, where she now teaches creative writing.

Read all of Still: The Journal's past reviews