Book Review

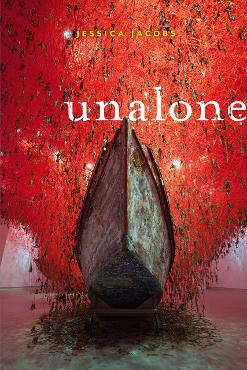

The wondrous, awe-inspiring, and at times frightful stories of the Torah have inspired writers for centuries. Poet and founder of the nonprofit literary organization Yetzirah: A Hearth for Jewish Poetry, Jessica Jacobs has entered into a conversation with our matriarchs and patriarchs in her new poetry collection unalone. Organized into twelve sections, like the book of Genesis, her poems follow biblical characters in a poetic, contemporary Midrash (a midrash is an ancient commentary on the Hebrew scriptures). Each section of Jacobs’ book is titled with the names of the “Parshiyot,” or portions, of Genesis and correspond to the images and specific moments that readers of the Torah will encounter in those sections, ranging from the days of creation, to the Tower of Babel, Noah and the flood, and Abraham and Sarah and their descendants, whose concerns range from hospitality and barrenness to loneliness and violence.

This collection opens with the poem “Stepping through the Gate,” which begins with the line, “Make a fence, said the rabbis, around the Torah,” which traditionally is understood as a means of protection, of guarding the holy Torah and keeping it at the center of Jewish peoples’ lives and preserving the core values of Judaism. Near the end of the poem, Jacobs writes, “Let every fence in my mind have a gate. / With an easy latch and well-oiled hinges.” Like much of unalone, Jacobs takes a traditional understanding of a topic or story and finds a way to open a new “gate” to provide a personal and contemporary perspective.

The speaker of Jacobs’ poems addresses and comments on the concerns and experiences of biblical ancestors, while finding ways to view them anew and empathize with their losses and heartache. At times didactic and at other times reflective and comparative, Jacobs’ poems hold the stories of the Torah up to our current moment as well as the speakers’ relationships with her mother, sister, lover, and God. Some poems, such as “So Jacob served seven years for Rachel and they seemed to him but a few days because of his love for her,” are titled using lines directly translated from the Torah. This poem invokes the love the speaker feels for her lover when writing about the patriarch Jacob’s love for his wife Rachel. Some poems, such as “No one’s loves, no one’s wives,” give voice to women who are silenced in the Torah – in this case, Bilhah and Zilpah, Jacob’s concubines.

In the poem “Will not the Judge of the Earth do justice?”, Jacobs describes a conversation between the speaker and her sister, who is a new mom and expresses an understanding for a woman who wrestled an alligator in the Everglades to free her son from being its prey. Jacobs threads this moment alongside a description of fire raining down on Sodom and how Lot’s wife would look back no matter what anyone said, as two of her daughters were still trapped in that city.

. . . When they passedin the tent, Isaac rubbed a remembered achein his shoulder and never again heldhis father’s eye. Sarah, smelling the imaginedashes on her husband’s fingers, the bloodin the crease of his throat, turned from him

in the night.

~Jessica Jacobs, unalone

. . . When they passed

in the tent, Isaac rubbed a remembered achein his shoulder and never again heldhis father’s eye. Sarah, smelling the imaginedashes on her husband’s fingers, the bloodin the crease of his throat, turned from himin the night.

. . . A visionof the future so certainit’s already past. Like my mother,decades beforeshe would forget her own nameor the fact she’d had children, saying,You’ll miss me when I’m gone.

Jamie Wendt is the author of the poetry collection Fruit of the Earth (Main Street Rag, 2018), which won the 2019 National Federation of Press Women Book Award in Poetry. Her manuscript, Laughing in Yiddish, was a finalist for the 2022 Philip Levine Prize in Poetry. Her poems and essays have been published in various literary journals and anthologies, including Feminine Rising, Green Mountains Review, Lilith, Jet Fuel Review, the Forward, Poetica Magazine, and others. She contributes book reviews to the Jewish Book Council as well as to other publications. She received a Pushcart Prize Honorable Mention and was nominated for Best Spiritual Literature. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Nebraska Omaha. She is a middle school Humanities teacher and lives in Chicago with her husband and two kids.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________