Book Review

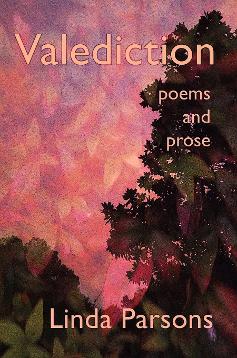

With its coherence of theme and consistently surprising language, set to the music of Appalachia, Linda Parsons’s new book Valediction is one of the most subtly nuanced books to come out of the post-pandemic period. For all of us who have felt the earth shift during this time, Valediction’s beautifully crafted poems provide the gift of solid ground.

The poet deftly brushes personal loss into the universal with a light almost unnoticeable stroke like carefully gradated shadings of value on a color wheel. The title poem of the book found in Part 1 is a gorgeous free verse lyric in which the voice of a dove provides comfort “cooing all’s well” after the speaker loses a beloved aged dog, “the first creature I saw when the needle was done / and my sheepdog limped into last light.” The dove, like the garden, “comes not to forbid mourning, / but trills core deep, beyond the senses, glances back to make sure I follow/its white-tipped tail.” The poet like the ocarina asks the reader to “bear all the light coming.”

The poet sets out on a pilgrimage through the worlds of animals, plants, and minerals. Ghosts are as vividly fleshed out as the gardens they haunt. Both humans and plants are richly textured, and the poems makes breathtaking leaps between the two:

The gardens seem to grow richer before the first frost, a last hurrah before the ghostly breath

passes over, the shrub and drift roses still hot pink and coral, nandina berries reddening for

Christmas, spirea and viburnum blood-tinged at the edges. This sometimes happens in those

who are dying, a sudden animation and presence called terminal lucidity. (“Visitation: Bright”)

The speaker is in love with the living world and with her ghosts, even those who behaved without skill, loving them for the “Bright living” within them:

I walked through the beds and laid my hands on the forest pansy redbud, mottled myrtles,

beauty berry and rosehips, the paperbark maple’s peeling scrolls. Each wrote its name

on my path. I thanked and blessed them for their bright living, even as we go forth to die.”

(“Visitation: Bright”)

Although Valediction is a book of elegies, it could just as well be titled “Bright Living,” a theology of flowers. The book takes the reader through a labyrinth, a meditative, botanical journey, searching for the sacred in both the living and the dead.

Particularly strong are the prose poems entitled “Visitations” which run throughout the four sections of the book, bringing the dead back to life, vivid as the sensorially rich gardens Parsons describes. The poem “Visitation: Mother,” in section 3 is particularly telling with its insight that “Sometimes the field of our story is equally ruined. We are sometimes the leaving and sometimes the left.” In lyric prose this poem imagines, like many of the poems in Valediction, a garden, lush with “wild-haired spirea, chartreuse in spring and summer with snowflake flowers.” Into this garden “fall fungus” appears. Human relationships arrive as well—in this case the speaker’s once destructive mother, now suffering from dementia. This mother no longer remembers the daughter who takes her hand, described as “silky.”

Valediction has a luminous, spiritual quality, but it is the earthy

language—precise and chiseled, with the earthy diction and humor

of Appalachia threaded through even the most somber poems—that

bring the poems to life.

Katherine Smith’s recent poetry publications include Boulevard, North American Review, Ploughshares, Mezzo Cammin, Cincinnati Review, Missouri Review, Southern Review, and many other journals. Her short fiction has appeared in Fiction International and Gargoyle. Her first book is Argument by Design (Washington Writers’ Publishing House, 2003). Her second book of poems is Woman Alone on the Mountain (Iris Press, 2014), and her third book is Secret City (Madville Publishing, 2022). She works at Montgomery College in Maryland, where she is poetry editor of Potomac Review.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________