Book Review

Walk a ways by yourself in the woods and hollers of the Appalachian mountains, and you quickly sense you’re not alone, maybe you’re even being followed. These hills hold presences and predators, prey and victims.

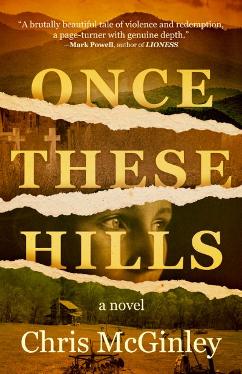

Chris McGinley unearths those buried fears in his debut novel Once These Hills, reviving the familiar formulas of crime fiction into a closer look at a changing Appalachian community. Instead of the usual male suspects, McGinley focuses on women as heroes, not just passive victims.

In 1898 in a remote eastern Kentucky mountain known as Boar Mountain, 10-year-old Lydia and her father make a remarkable discovery, uncovering the grave of an indigenous woman mummified in a bog. She was buried with a stone ax that she probably used herself. Lydia and her father leave the body and artifacts undisturbed, but later the mother worries they may have unearthed a curse on their community:

“Now, did you touch the body, Preston? Were you careful when you placed the earth

on top?” It was concern for her family that drove her to ask. She worried about what

her husband and daughter may have unleashed. There was danger in defilement,

she said.

We get short flashbacks to “Long, Long Ago,” when the nameless indigenous woman and her husband roamed these same woods. Lydia unknowingly follows in her archetypal ancestor’s footsteps as she hunts for hares with her trusty bow and arrow and an innate instinct, reminiscent of the hunter-goddess Artemis from Greek myth.

In 1901, Lydia’s bucolic life is shattered when news reaches the remote mountain that convicts working on the new Railroad have escaped and may be headed their way. Here we meet the villain and driving engine of this fatalistic narrative – Burr Hollis, a sadistic killer with a seemingly insatiable bloodlust. Lydia’s life is forever changed when Burr and his two cronies attack her family’s remote cabin.

Some readers may shy away from the graphic violence and sexual assault here, but McGinley ratchets up the tension as this book quickly becomes a page turner. Lydia is transformed from an innocent mountain girl into a kind of mythic avenging angel. Willing to mutilate herself to slip her shackles, she dispatches one of her assailants with her unerring arrow. But Burr and the other man melt away into the woods as the inept manhunt mounted by the sheriff in the town of Queen’s Tooth dwindles away.

But Black Boar will never be the same. The violence that Burr visits on the community is replicated in the industrialized rape of the landscape that the Railroad brings with timber companies. Lydia flinches from the carnage when she hikes a few years later to the top of the mountain with her beau, Cole, and looks down on the clearcutting devastation. Trees are mown down, slash piled away, the waters polluted.

McGinley offers an environmental eulogy for the devastation of a virgin wilderness. And like Cole, we witness that mythic beauty of the blossoming Lydia as she dips naked into the river:

Rivulets fell from her hair and breasts and shiny droplets clung to the hair between her

legs. Far in the distance were the hills in their browns, yellows, and reds. It was as if she

had come from them, Cole thought, like some figure from a story, some Greek myth.

He saw it all at once, this one complete image of her, a beautiful creature born of the hills.

Yet, like the buried bog woman, there may be deeper forces of darkness at work on the mountain. Lydia herself encounters the mythic animal that gives Black Boar Mountain its original name. She is charged out in the woods by the beast, which somehow relents in goring the girl to death, but marks her for life.

The story becomes one of Lydia’s growing up in the aftermath of violence and grief. With her mother, Inez, traumatized by her rape, they find refuge with their closest neighbors, Clytie and Cornelius.

Again, the women take center stage as better hunters and stronger characters than their menfolk. Clytie becomes a surrogate mother to Lydia as she grows up, grows more proficient as a hunter putting food on the table.

McGinley has a prose style as clean as a bone, but authentic to the

speech and ways of mountain folk. Here we get wonderful details,

from how to field-dress and cook a bear into a community burgoo

to the proper way to heal the poisonous bite of a rattlesnake.

Dale Neal is the author of the novel Kings of Coweetsee, coming in summer, 2024, and The Woman with the Stone Knife in fall, 2024. His other novels include Appalachian Book of the Dead, shortlisted for the Thomas Wolfe Literary Award; Cow Across America, winner of the Novello Literary Award; and The Half-Life of Home. His short stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in Our State, Smoky Mountain Living, North Carolina Literary Review, Appalachian Journal, Carolina Quarterly and elsewhere. He earned an MFA in creative writing at Warren Wilson College. A retired journalist, he lives in Asheville, North Carolina.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________