Book Review

Mosquitos circling nests of eggs,

dragonflies feasting from dusk-blurred water.

Why did no one teach me that behind

every miracle is a god taking everything

it wants?

Savannah, my mother would say,so beautiful General Sherman could not watchit burn. Perhaps this is why we stayedin this city of rain-torched oaks

Saturday blooming before them likea heaven that could seize them up—raped girl, ghost story. Even Shermanwould not burn it down.

The verb for it is glossing his Chrysler down right lacquered upwindows at half-mast like cigarettes tight-rolled into a T-shirt sleevethe whole rhetorics of it rust then katydids flitting their wingsrhapsodic. One of those nights where even the moon threw a glare

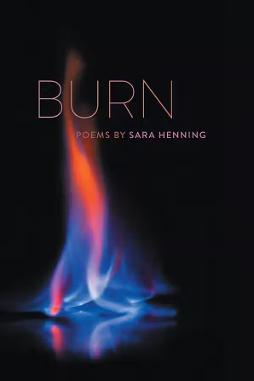

The work in Burn is raw and searing. The themes are relatable to most, but there is an overtone of overcoming darkness that is especially thrilling in these poems.

Loving a man is like loving a body with the threatof ash all around it—you’re his kerosene.His flash point glimmers when you touch his skin.But I’m at a safe distance: no smoke in my kitchen.

Bess N Mobley is a third-year PhD English student at Claremont Graduate University. She has published poems in The Bayou Review, em-dash, and Amazing Poetry. She has also published original artwork in em-dash and Tidings Collective and was asked to draw a book cover for Punk Hostage Press. She’s published numerous poetry reviews in journals and blogs all over the country. She has an MA from Purdue University, and her academic work focuses on female and queer fiction writers who place themselves into their own story worlds. Bess enjoys anime, manga, painting, hiking, biking, watching movies at the theater, and random adventuring.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________