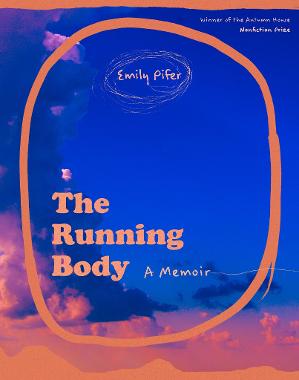

“How, anyway, do you build something whole out of a series of fracturing? This was never going to be a story; it was always going to be a scratching, a clawing.” So reflects Emily Pifer in her debut memoir The Running Body, winner of the 2021 Autumn House Nonfiction Prize. In this book, Pifer considers her upbringing in Ohio and West Virginia as she discusses her past-present-future as a runner, and she circles, through the ovals of the running track and her lyric paragraphs, around “the summer” when her body became “the running body.”

Across the six sections of her memoir, Pifer turns and re-turns to that pivotal summer when, as a rising track and field collegiate runner at Ohio University, she travels to Eugene, Oregon, for the National Track and Field Meet and—surrounded by a sport, a coach, teammates, friends, and white America at large who all celebrated thinness—lost her body and became the running body, “something other than me. This hard, sharp thing.” With her, we watch “the running body as it floated around a curve, easily working through a three-mile warm-up. ‘That’s called zero body fat,’ the coach continued.” With her, we “saw the body that was once mine crossing an invisible line between dream and reality.”

Pifer’s first (and longest) section follows her life from her childhood in Scott Depot, West Virginia, to her family’s move to Ohio when she was seven, to her coming-of-age and moving to college, where, once she “signed a contract to run at Ohio University, I adopted a sense that my body was no longer my property.” Ideas of property and belonging appear across The Running Body as Pifer travels between West Virginia, Ohio, Wyoming, Oregon, and New York. West Virginia, and specifically her great-grandparents’ farmhouse, surrounded by “slow-rolling hills” and a humidity so dense “its thickness holds the body,” is a touchstone. This land acts as a bell—like the bell of each lap of a track event—to turn a line into a spiral, where we always are both home and newcomers, making and finding meaning within a whirl of time.

During her first year at Ohio University, Pifer began to increase her mileage and decrease her food intake, earning faster times, praise from her team, and her transformation into “the running body.” As her training increases and eating decreases, as readers find in the second section, she suffers a series of fractures, including one of her pubic bone: “a fracture cutting right up the center of me.” These fractures ignite a series of events that take her out of competitive running and into another painful process of reckoning with who she/this body is now if they both are and are not “the running body.” These hard questions continue across the book’s four remaining sections, avoiding any easy answers.

As her memoir progresses, each section approaches this pivotal summer and its aftermath with different knowledges. In her second section, Pifer recounts her series of bone fractures by fracturing her narrative with the found texts of email exchanges and medical records; in her third section, this fracturing extends into her relationships and work, until she at last “started to try to tell the story of what I had done to my body.” In her fourth section, Pifer considers the erotics of exercise as she pursues recovery through gym workouts and heavy lifting; in her fifth section, she examines the role of patriarchy and capitalism in the relentless looking and objectifying of (women) athletes; and in her final section, she contemplates how magical thinking converges with faith and how to continue after both are lost.

For: grief is never linear. Elizabeth Kübler-Ross describes grief in her pivotal On Death and Dying, as paraphrased by Pifer, as “a cycle—made from not one circle, but many, concentric and overlapping, sticky and slippery.” So, too, could one describe the long-distance track races where Pifer excelled, where one race might hold 25 laps of the same four-hundred-meter oval and yet, when the running body lights up, locks into its practiced rhythm, and opens to the inevitable pain, these concentric loops become portal and vortex, an epiphanic experience, for “while the body is running the instants do not just stretch but come undone and blur to one long and flat instant of being.” A lifetime can bloom and implode in seconds. In a summer.