Book Review

Coweetsee County lies at the tail end of the state, wedged deep in the Blue Ridge, as if a divine crowbar hadprized open the high mountains for human habitation. Here, you find us, a few remaining families hangingwhite-knuckled onto steep sloping, hardscrabble farms. Living back of beyond, we don’t consider ourselvesa backward people, but as the keepers of a lost kingdom.

Once you had to take the slow-bending River Road east and west of town, the only way in and out of Coweetsee.Then the Kingdom cracked open when the Feds moved the mountains and poured six lanes of concrete so afamily of four in a minivan from Cincinnati could blow through here at 75 mph on their way to Disney World.Only the more adventuresome ilk might exit the beaten path to gape at our fall leaves or our many barns—evenfewer stop by the Coweetsee County Historical Society.

Shawanda was the best quilter in the county and her work worthyof the Smithsonian, but she was often overlooked because of the blackness of her skin, and how that doesn’t jibe with the official white-bread version of hillbilly Appalachia.

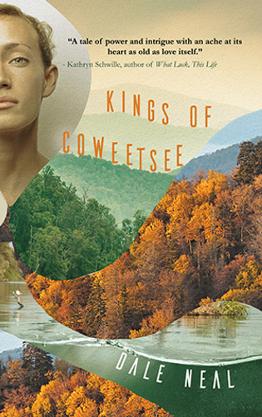

~Dale Neal, Kings of Coweetsee

Shawanda was the best quilter in the county and her work worthy of the Smithsonian, but she was often overlooked because of the blackness of her skin, and how that doesn’t jibe with the official white-breadversion of hillbilly Appalachia.

Tommy Hays is the author of four novels: The Pleasure Was Mine (St. Martin’s, 2005), In the Family Way (Random House, 1999), Sam’s Crossing (Atheneum, 1992) and middle grade novel What I Came to Tell You (Egmont, USA, 2013). He was inducted into the South Carolina Academy of Authors and named to the Order of the Long Leaf Pine, the highest civilian honor bestowed by the governor of North Carolina. He’s retired Executive Director of the Great Smokies Writing Program and Lecturer Emeritus in the Master of Liberal Arts program at UNC Asheville.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________