Book Review

When I traveled in Europe in the 1990s, one particular, if mundane, sight never failed to move me—couples carrying a single duffel bag, each holding a handle, as they made their way on and off the trains. As I hefted my backpack like an overburdened turtle, I would envy them. Not so much for their couple-ness—even in my 20s, I liked traveling alone—but because of the intimacy and trust implicit in the act of mixing together belongings and sharing their weight.

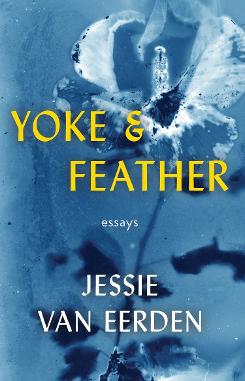

This memory came to me as I read writer Jessie van Eerden’s latest essay collection, Yoke & Feather, in which disparate entities are mingled and burdens shared. This volume, van Eerden’s second essay collection and fifth book, features 21 braided essays, 22 if you count the Prologue, which I would, as it too features the braided structure.

The title could tempt the reader to view the collection in terms of the sundry binaries evoked by the dualistic image of feather and yoke—light and heavy, profane and sacred, ease and burden, weightlessness and gravity. The braided structure, however, renders such a reading impossible, for a braid typically has at least three strands, if not more.

And what strands they are. Consider the elements brought into conversation with each other in “A Thousand Faces,” originally published in River Teeth and one of the strongest pieces in the collection. As the speaker and her lover canoe through the Rio Grande’s Boquillas Canyon, her thoughts move among the COVID pandemic, the border with Mexico, a burgeoning romance, and Moses watching God’s back as he passes by, the whole mixed with various outside references including Barry Lopez, Teju Cole, Emmanuel Levinas, and Judith Butler.

Another notable feature of the collection can be found in the vivid reimagining of stories from the Bible. Well-known figures are most often featured . . . Ruth and Naomi, the hemorrhaging woman who touches Jesus’s cloak, the woman with the jar of nard, a newly resurrected Lazarus, to name a few. However, lesser known andeven imagined characters find their place as well.

We cannot be less than we are, less a mother, less a child—but maybe we can be more than weare named. And if our hands reach to touch and do touch, so gently, another, it’s as if a new meaning congeals with each moment of contact, a new nameless form of relation fused between two that wereonce strangers, as even my mother and I once were, at the very start.

They tell Maud together about her period when it comes. Mary with a gift of a silk scarf and akingfisher feather. And Martha with gravity and a voice of decorum and dust, grave but alsocomprehensive anatomically.

Laura Dennis is a Kentucky writer, mother, Mimi, and professor with family roots in northern Appalachia. Her work has appeared in a variety of publications, including Change Seven, Northern Appalachia Review, The McNeese Review, Still: The Journal, and The Red Branch Review. She reviews books for several publications and co-edits book reviews for MER. She enjoys music, photography, hiking, and spending time with her friends, family, and pets.