Book Review

University of Georgia Press, 2023

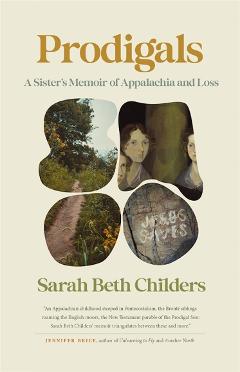

West Virginia native Sarah Beth Childers’s memoir Prodigals is about love and death, specifically the love Childers felt and still feels for her younger brother, Joshua, and the deep sadness she experienced when he tragically died of suicide at age 22.

Like Childers’s earlier book Shake Terribly the Earth (Ohio University Press, 2013), this collection of linked lyric essays focuses on faith and family, but the focus of this book is more specifically on Childers’s brother and what it was like to love and lose him. Prodigals is framed by the Biblical story of the prodigal son.

Like the prodigal son, Childers imagines that her brother will return to her and her family after his death, though she agonizes over the when and how. She believes in an afterlife, but she wonders if her brother will want the promise of that, and, if he returns, which version of Joshua, who she lovingly nicknamed Smoo, she will see. As a child, Joshua wanted to be a singer and then a musician. As an adult, he hoped to be a filmmaker. But school was a struggle for Joshua who didn’t always attend classes or turn in assignments. One of Joshua’s other sisters, Rebecca, even went so far as to take a class with him at Marshall University in an attempt to help him pass, in part because, “During Joshua’s previous semester, he’d reveled in the freedom of the dorms, but he hadn’t gone to class, and he’d drunk so little water he’d contracted a near deadly kidney infection.”

Childers’s memoir draws on not only her own childhood in Appalachia but also on the life and death of the literary Brontë siblings and the parallels between their lives and her own. In particular, she compares her brother to Branwell Brontë, who was widely known as a famous failure and details how her young, ambitious, but difficult brother was like him. Like Branwell Brontë who yearned for the big city of London, Joshua dreams of living in New York City, and he does get to visit the famed city once, but he never lives farther away from his rural West Virginia home than the nearby dorms at Marshall University. “Since I lost my brother, I’ve often feared his short adult life was like Branwell’s, all frustrated hope and wasted talent,” Childers writers. But she also realizes though Joshua’s life was filled with turmoil and angst, there was more to it than that: “I can’t help focusing on the turbulent unrestrained misery of these men. But I’m wronging them all if I forget their luxuriant, exuberant joy.”

Childers, on the other hand, identifies in some ways with the more responsible and successful elder sister, Charlotte Brontë. Like her brother, Childers also tries to leave her home but initially finds herself returning until she can find surer footing. Her first attempt to strike out on her own is when she decides to enroll in an undergraduate engineering program at Virginia Tech, away from her beloved West Virginia. Deciding that both the school and the major aren’t for her, she completes her undergraduate history degree at Marshall University. She attempts a graduate program in history in Lexington, Kentucky, but decides not to complete that program either. Finally, she successfully breaks away from her close-knit family when she enrolls in the MFA program in creative writing at West Virginia University. Childers writes, “West Virginia University was eighty miles further from my parents’ house than the University of Kentucky, but it felt closer. I felt soothed by the steepness of the sidewalks and streets, the brown river that traced the length of the city.”

The book is rich with stories of faith, failure, and redemption, both from those the author knew and those she heard and read about including that of televangelist Jimmy Swaggart. Before his “fall from grace,” Childers and her mother used to watch Swaggart on TV, and it was from Swaggart that Childers’s family learned about the treasured Bible Storybook where as a child she read and reread the story of the prodigal son, which would come to shape and frame her understanding of her brother’s death. Like many fundamentalists, Childers writes that Swaggart, “viewed his sex addiction as demon torment and sin.”

A mixture of flash and longer pieces, the essays in this collection are not only tied together by the similarities between the Brontë family and Childers’s own but also by Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth. Zeffirelli, Childers notes, was a kind of prodigal too: “Franco Zeffirelli was raised in a devout Roman Catholic home, but he left God. At forty-six he was in a horrible car wreck. As Zeffirelli bled in his car, he told God, if you let me live, I’ll make films for your glory.” Zeffirelli, who is known for theatrical releases like his racy 1968 Romeo and Juliet, survived and kept his promise by directing the made-for-TV mini-series Jesus of Nazareth, which Childers watched over and over. After her brother’s death, she pictured Joshua like the demon-possessed boy in Zefferelli’s version of that story. She writes, “Watching the film now, I ignore Jesus and focus on the boy. After Jesus kicks out the boy’s demons, he lies still on the stone floor, apparently unconscious.” Likewise, as Childers’ brother struggled with what she believes was undiagnosed mental illness, she too longed to have a brother who was well and whole. She writes, “Holding Joshua’s body to the floor, looking at his anger-wild eyes, I sometimes wondered if the brother I loved would come back.”

Woven throughout the memoir of grief and loss is the author’s own story of finding her first love, Gideon, in the hills of Morgantown, West Virginia during her graduate studies, and breaking up with him shortly before her brother’s death. In the wake of her brother’s suicide, Childers turns to Gideon once again and hopes for a reconciliation. But the author’s desire to settle down and have children is at odds with Gideon’s hesitation to commit. After her brother’s death, Childers’ grandmother asks if she is still dating Gideon and then perceptively notes, “When you brought that boy here to meet me last year, I kept thinking, she loves that boy, and he’s scared to death of getting married.”

This memoir deals not only with the author’s life before and with Joshua, but her subsequent life without him. Even several years after her brother’s death, the author still feels the ache of missing her brother. She writes, “Three years now since my brother killed himself. Sometimes my grief is still obvious. I brew iced green tea, then forget the pitcher on the counter until gray mold floats across the surface.”

The author does not sugarcoat the realities of her family life or romanticize that life with her brother, who likely suffered from mental illness like the author’s maternal grandmother did, could be difficult. He could be angry. He could be insensitive and lazy. At times, he ruined special occasions like the author’s sister’s birthday worrying the family that he might never return. When teenage Joshua disappears for hours on the same day that Childers is supposed to attend the scholarship dinner at Marshall University where she is the guest of honor, Childers realizes, “I knew Joshua didn’t mean to ruin my evening; he just didn’t have the energy to care about my life.”

Like her deeply religious mother, despite her doubts, the author, who is now an assistant professor of English at Oklahoma State University-Stillwater, seems to also believe that, in the end, her prodigal brother will return and that she can finally show him that she loves him once again. “When Joshua died, I lost the emotionally closed-off, sometimes violent, twenty-two years-two-months-two weeks-old brother I knew, and I felt the loss again of the brother I’d adored as a child.” Prodigals: A Sister’s Memoir of Appalachia and Loss should resonate with anyone who has loved deeply and who has struggled to make sense of the meaning of life in the wake of a loved one’s death.

Lori D'Angelo is a grant recipient from the Elizabeth George Foundation and an alumna of the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley. Recent work has appeared in Beaver Magazine, Bullshit Lit, Chaotic Merge, Ellipsis Zine, Idle Ink, JAKE, Litmora, Rejection Letters, Thin Veil Press, and Voidspace. Find her on Twitter and Bluesky @sclly21. She lives in Virginia with her family.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________