Book Review

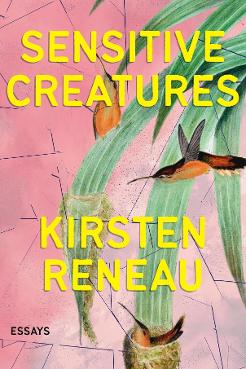

With her debut essay collection, Sensitive Creatures, West Virginia native Kirsten Reneau finds numerous parallels between inhabitants of the natural world and potent events in her own life. Through these comparisons, Reneau is seeking out a new way in which to understand these facets of her life, a way borne of grist and resonance.

With a hybrid approach that blends scientific detail with personal essay, Reneau explores challenging subjects like sexual violations, self-sabotage, difficult relationships, and the fallout of trauma. These moments of linkage between the natural world and personal struggle are sometimes direct, sometimes more oblique. But perhaps what’s more important than any specific point of comparison is the larger attempt that Reneau makes through the lens of pointed inquiry—to discover another way to live.

“How the Cicada Screams” describes the author’s driving urge to be heard at a time when dark experiences had threatened to silence her. During a summer of turmoil, she takes refuge in a forest at night. There, “the cicadas spoke.” She has come to isolate herself, but the cicadas are deafening. “Once I screamed back. I was so loud that the dogs nearby began howling, too,” Reneau writes. “Then we were all just making noise, a symphony of animals trying to be heard, trying to bait the universe into giving answers to a question I didn’t know how to ask.”

Several other essays detail the toughest consequences of sexual trauma, as in “To Survive Hypothermia, You Must Ignore Everything Your Body Tells You.” This striking micro essay describes a fragment of the author in a state of volatile honesty, as she surfaces for a moment from an era of emotional and physical numbing. At this time, she sought oblivion, denying every healthy impulse, “always drinking and drunk then, making my body a Molotov cocktail to be thrown at whoever would catch it, open-palmed.”

In Sensitive Creatures, Reneau finds metaphorical resonance between incidents in her own life and dolphins, monarch butterflies, sparrows, comb jellies, hummingbirds, and more. In some essays the connections between the natural world subjects and the personal narrative details are clearer than in others. A piece that links the lives of fireflies to a fraught long-distance relationship, for example, doesn’t quite pull its metaphor together. And, certainly, the slimness of this collection leaves room for further development. When similar essays of this kind appear one after another, each individual piece runs the risk of seeing its impact lessened.

Reneau links the ephemeral nests that hummingbirds build to a new apartment she’s settling into with her partner—a circumstance as precious but also as subject to changeable conditions as one of these fragile nests, which is shaped to fit the contours of a particular time

and place: “I realize I’ve grown into this place, and now I worry that

we will continue to grow until it breaks around us.”

However, Reneau does break up this pattern on occasion with essays that offer formal, structural experiments. True to its title, “Bar Bathroom Graffiti in New Orleans: A One-Year Catalog” riffs on a dated list of short messages that the author found scrawled on bathrooms walls in various bars over the course of a year. Decoding these messages, Reneau acknowledges in herself “the urge to create something that feels permanently heard.”

“Quiz: Do You Have a Healthy Relationship to Sex?” explores the evolution of a young woman’s perspective on sex through the unmistakable shape and structure of a multiple-choice fashion magazine quiz. What’s framed as a shallow enquiry into healthy attitudes on sex becomes a detailed accumulation of memory and implication, revealing the ubiquitous and confusing messages about sexuality that crowds every young woman’s life, beginning in childhood. The result is unexpectedly effective, providing some of the richest details in the collection.

Through subtle shifts in tone, the essays do grow more hopeful as the book progresses. Reneau links the ephemeral nests that hummingbirds build to a new apartment she’s settling into with her partner—a circumstance as precious but also as subject to changeable conditions as one of these fragile nests, which is shaped to fit the contours of a particular time and place: “I realize I’ve grown into this place, and now I worry that we will continue to grow until it breaks around us.” Reneau frames her dilemma in terms just as vulnerable as a hummingbird’s, but in her willingness to risk intimacy, we recognize an openness that would not have possible for her in the earlier essays.

The final pair of essays cast their focus toward the night sky and the deeply personal ways that we often write our own histories onto the vast starscapes above us. “To Outline the Moon” is a tender, atmospheric remembrance of formative times Reneau spent with her father and uncle in West Virginia—hiking through Monongahela National Forest’s dense woods, sharing poker nights, and stargazing in dark fields.

In “Scorpius,” the book’s closing essay, Reneau stands underneath the stars and, through her imagination, projects herself into the battle portrayed in constellation form overhead—between Orion and the scorpion. “The two will never be seen in the night sky at the same time, but they both are in the sky all the same,” she writes. “The constellations, resurrections of the dead, rise, and I look for myself—somehow still alive—reflected back in them.”

Throughout the collection, Reneau uses formal hybridity as a way to explore the branching-off of selfhood and identity that can occur as a result of personal wounds. The legacy of trauma in a human life is a dominant subject throughout the book, and at times, that legacy seems almost deterministic. “Unlike the butterfly or moth, the cicada has no pupal state,” Reneau writes in an early essay. “Rather, it is one single moment of change that sets them up for the unbearable weight of being alive.” At times, Reneau’s choices of metaphor imply that moments of trauma impose a kind of sealed fate, but the extent to which Reneau views her own experiences this way is unclear.

What is clear, however, is that the essays of Sensitive Creatures represent a promising debut. Unlike Reneau’s pupa-skipping cicada, a writer’s body of work is not bound to a “single moment of change,” and it’s easy to imagine an exciting trajectory of growth ahead for Reneau’s literary voice.

Emily Choate’s fiction appears in storySouth, Mississippi Review, Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Rappahannock Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere. She writes reviews, features, and interviews for Chapter 16, and other nonfiction appears in Atticus Review, Longridge Review, and Nashville Scene, among others. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. One of the founding editors of Peauxdunque Review, Emily holds an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College and was a Tennessee Williams Scholar at Sewanee Writers Conference. She lives near Nashville.