At night when I rock my nearly two-year-old daughter to sleep, she often calls out my name shortly before drifting off. “Ammi?” she asks, as though to confirm I’m still there. And I answer her in the language of my parents, in the language I speak with the vocabulary of a 4th grader; I tell her, “Ammi’s right here. Ammi is always with you.”

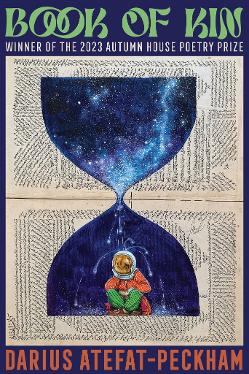

It’s a promise I make full well knowing that it is not one I am actually in control of. And it’s the promise I found myself thinking about again and again as I read Darius Atefat-Peckham’s poetry collection, Book of Kin, released by Autumn House Press in fall, 2024.

In “Here’s a Love Poem to the Garden Snail,” Atefat-Peckham writes, “Can a person be a person without memories?” This is but one of many questions about the legacies and layers of grief that sit at the core of this collection. His poems explore the grief that accompanies losing a mother and brother early in childhood; the cultural bereavement that comes from being unable to fully access the country, the culture, the language of his mother’s family. But alongside that grief, there is this clarion call to love, to holding those still here with a kind of tenderness.

I knew before reading that I couldn’t review this book through the lens of a poet. That while I appreciate poetry, commentary on form or style is not a skill I possess.

I thought I would read through the lens of neighbor. I grew up just 40 miles down I-64 from Atefat-Peckham, and imagined there might be shared space between Iranian-Appalachian and Indian-Appalachian existence, between belonging and unbelonging in Appalachia.

I did not know that I was going to read this collection through the lens of mother. Did not know that it would show me all the ways in which mother and child’s identities are intertwined, shape one another, even if that shape is created by absence.

This fall, my partner Laura and I both transitioned to new jobs. Our daughter Kahani started daycare. The three of us all got COVID, one after the other after the other. Parenting has required a kind of relentless presence that exhausts me. Leaves no room for writing, no room for self. I attend to my job’s needs, to my child’s needs, or I am asleep. But my child doesn’t sleep, so mainly I just attend.

Which makes reading the following lines in Atefat-Peckham’s poem “Mother,” land in an entirely different way than it might have before becoming a parent: “If you long for time enough, absence becomes a kind of presence. Distance taut as a line between us. No cord is broken.”