Interview

Interview with Jeff Daniel Marion

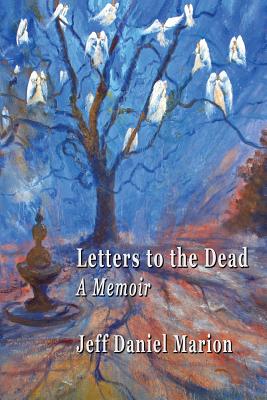

© Doug Berryhill. Used with permission.

Jeff Daniel (Danny) Marion has spent nearly all of his life in East Tennessee. Born in Rogersville (Hawkins County in northeast Tennessee) in 1940, he lived there until moving to Knoxville to attend the University of Tennessee. After graduation he taught high school English for a few years, before he settled at Carson-Newman College (now University) in the late 1960s where he taught English and creative writing classes until his retirement in 2002. At Carson-Newman he was named distinguished-poet-in-residence, created and edited a literary magazine (The Small Farm), advised and reshaped the English Department’s literary journal (The Mossy Creek Reader), worked as a poet in the schools, established and directed Carson-Newman’s Appalachian Center, and mentored hundreds of students in the ways of reading and writing. He has published nine collections of poetry, several essays and works of short fiction, and a children’s book.

In 2013 Carson-Newman University honored Danny Marion with a two-day festival that celebrated his life and literary legacy. Those festival tributes and analyses (and others previously published) were collected in the new volume Jeff Daniel Marion: Poet on the Holston and edited by Jesse Graves, Thomas Alan Holmes, and Ernest Lee (University of Tennessee Press, 2016). Jesse Graves writes in that book:

Marion’s poetry has been considered mostly in the context of Appalachian literature, and few writers have done more to establish and promote a sense of regional identity in their work. However, this identification risks offering a limited view of Marion’s writing, which in fact engages with several national and global literary traditions. . . . Marion’s work is overdue to be considered as an accomplished representative of the central grain of American literary tradition, the grain that begins in Ralph Waldo Emerson, and descends through Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, out of the Flowering of the New England Mind, the American Renaissance, and into our contemporary literature.

Still: The Journal asked Marion to comment on some questions related to the release of this new book. We met at his home on the Holston River in Jefferson County, Tennessee. While we talked we watched herons, egrets, and kingfishers work the river for their supper.

(Editors' Note: This interview appeared in our 21st issue, Summer 2016. We are saddened to report the passing of Danny Marion on July 29, 2021.)

Still: What did you learn about your work as a result? Were there any revelations or ways of seeing yourself as a poet or teacher that you hadn’t known before?

JDM: I’ve always maintained that a teacher is a sower of seeds. Sometimes we sow in rich fields, sometimes in barren and rocky ones. But sow the teacher must—that’s the nature of the profession. What the teacher rarely if ever gets to see is the result of the sowing. The sowing must be done as an act of faith in the process. What the Festival allowed me was the rare and precious opportunity to see the fruit of some of those seeds I sowed long ago in faith. That is a rare and unique gift I’ll always value.

Still: Poet on the Holston examines your labors as writer, teacher, and editor, but also offers insight about your work as photographer and includes many of your photographs in the collection. In fact, the cover image is one of your photographs. Tell us how photography and writing are related for you.

Still: You mentioned in the interview with Poet on the Holston co-editor Jesse Graves that you are working on a new poetry collection titled Ground Observer. How will this new set of poems relate to or distinguish itself from your previous nine collections of poems?

JDM: I don’t know the shape of a book of poems until I’ve accumulated enough work that forms a pool I can choose from. Then I look through the poems noticing patterns, similarities, possible groupings, etc. I’m not a writer who gets an idea for an entire book of poems and works from there. I do know some very fine poets who work that way, but maybe I’m a kind of Johnny Appleseed who plants a seed here and there and after time finds an orchard grown up around him and then goes back and gathers the apples. But since the beginning of my work I’ve been a ground observer, a person who notices and tries to pay attention to whatever is around me and wants to render it in a language and form such that the reader cannot help but see and experience it.

Still: “Land of Lost Content” is the title of your memoir-essay that opens Poet on the Holston, and it seems to be guided by a series of questions. Here’s one: “I keep asking myself where the rings end: where do they go, these ripples from a bobber cast upon the water, these rings intertwining in a quilt whose cold cloth warms us through long and starless nights?” What answers did you discover or hope to discover in unearthing all those rings and circles of stories in that essay?

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview Still Life

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Contest Masthead Submit Feedback

_____________________________________________