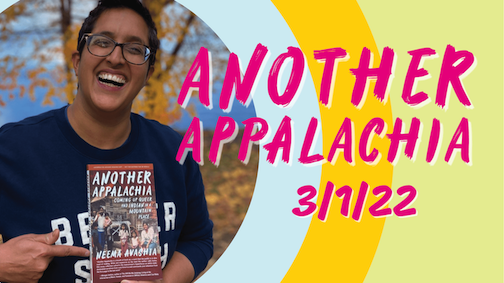

Still: The Journal: What do you want readers to know about your collection of essays that comprise Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place?

Neema Avashia: So many things. First, I want them to know that for me, a queer Indian woman, the daughter of immigrants, to be writing a book is a really heavy notion. For a Desi woman to write, and to publish, and to put truth on the page is pushing back against gender norms regarding whose voices matter, and whose voices do not, that have existed for multiple millenia. So this process feels risky and scary, but also really important.

Secondly, I want them to know how hard I have tried to make sure that I hold the folks who show up in these essays with empathy, how important it has been to me to implicate myself seven times over for every one time that I’ve asked a question, or interrogated a choice, of someone else. And lastly, I guess I want them to know that this book is a kind of love letter to place, and to people. Not blind love, or rose-colored love, but rather, bell hooks’ definition of love: “When we choose to love we choose to move against fear–against alienation and separation. The choice to love is the choice to connect–to find ourselves in the other.” My hope is that in reading this book, in exploring the questions that it asks and attempts to answer, folks will find greater insight into their own relationships, their own identities, and thus, be brought closer together.

Still: We heard your reading for the West Virginia University Center for the Humanities recently, and you talked about how your immigrant parents encouraged you to practice “accommodation without assimilation” while you were growing up in West Virginia. Can you talk about that for our readers?

Neema: The best way for me to describe this is to explain what dinner looked like in my house growing up. We ate the same thing for dinner every night–a Gujarati meal known as daal (lentils), bhath (rice), shaak (vegetables), and rotli (a kind of flatbread). The type of lentil and the vegetable varied, but the composition of the plate was always generally the same. But the longer we lived in West Virginia, the more what counted as shaak started to evolve. Sometimes it might have been fried apples. Sometimes it was stewed rhubarb. Sometimes it was fried green tomatoes, but they were made with mustard seeds and coconut and chickpea flour. Sometimes collard greens subbed in where colocasia leaves would have been more traditional. Appalachian cuisine found its way onto our plates, but in ways that still fit within the composition of the existing meal.

I think this is effectively also what my parents taught me about how to navigate identity and culture growing up. They taught me Gujarati, their first language. They raised me steeped in the traditions of the Hindu faith, particularly those around non-violence and vegetarianism. They made sure I had deep connections with other folks from our ethnicity–that I saw myself in the world around me. But they also encouraged me to build relationships outside my immediate community–my neighbors and classmates–and to build understanding of Appalachian culture, and to make space for the ways in which those relationships and that culture could enhance and deepen my own identity. I might be the only Indian person in the world who grew up playing Appalachian folk music on my guitar, and I am that way because my parents saw Appalachian culture, and Appalachian people, as enriching, instead of something to be wary of.

And…now I’m hungry. :)

Still: Tell us a little about how you came to writing essays about your identity and community, and can you talk about how you managed to put a book together while teaching full time in the Boston public school system?

Neema: I’d be lying if I didn’t say that Hillbilly Elegy, and my deep anger about that book, wasn’t a big impetus for writing my own book. I read a book that was purportedly about the place where I grew up, and the people I grew up with, and I found both the people and the place as Vance rendered them to be virtually unrecognizable. And in some ways, I think it made me realize that if I wanted there to be stories about the very particular corner of West Virginia where I grew up–the chemicals part, and the Indian immigrant part, and the queer part, and the way all those things went together–then I needed to stop stewing and start writing. There aren’t many of us who grew up at those intersections, and I realized that if one of us didn’t articulate the story, it wasn’t ever going to be articulated.

Once I came to that realization, it almost felt like I couldn’t stop myself from writing. I would sneak out of bed early on Saturday mornings to write before my partner Laura woke up. I kept running notes on my phone of bullet points for essays, and then stayed up late at night turning those bullet points into narratives. I knew that I needed structure and community to write, so I would sign up for writing classes that ran way too late for my 5:30 a.m. wake-ups because they forced me to write to deadlines, and to share my work with a community of writers and get feedback on it. I went to places like the Kenyon Writers Workshop and the Appalachian Writers Workshop to see how my words landed in spaces closer to the place where I grew up. Sometimes I look back and I don’t understand how I was able to be so productive (and I wonder/worry about whether I’ll ever be that productive again!), but I think that the need to tell a different kind of Appalachian story was a kind of catalyst that just kept pushing me forward.

Still: So, a craft question: Your collection starts with an essay written in second person, a tricky point of view to pull off successfully. How did “Directions to a Vanishing Place” evolve?

Neema: Driving was such a big part of growing up. Things were far away from each other. There wasn’t a whole lot to do in terms of entertainment. So driving was a lot more than just a means for getting from place to place. It was a way in which I built relationships with people, and with the place where I grew up. David’s truck (featured in “Wine-Warmth,” which you all gave its home!), Mr. Bradford’s Jeep, the Schreck’s giant blue van, Amanda McNeel’s hatchback Tercel that we used to fit nine people into for summer morning rides to basketball practice. Those vehicles are as much a part of evoking place for me as homes or geographical locations are.

When I started to write the essays in this collection, it felt like one of the first things I needed to do was to put readers in relationship with the place I was writing about, and in some ways, it felt like the only way to do that was to take them there. I wanted to put them in my car and drive them down the road and point out the landmarks and situate them, so that as they read the rest of the stories, they read them on solid footing, knowing the place I was talking about as well as I could possibly show it to them. So…directions. Directions became the way to show them, and the form for directions is always the second person. It is a tricky place to start, but I also think that starting there gave me permission to experiment with form again at different points in the collection, with an essay that is structured like a spice catalog, with a list essay, with multiple collage essays. By using second person right at the outset, I feel like I’m letting the reader know that this isn’t going to be a traditional ride or read.