Book Review

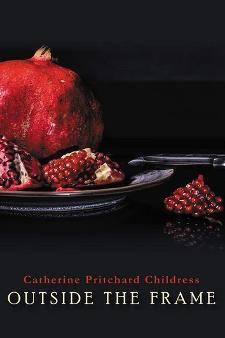

It’s surely no accident that the cover of Catherine Pritchard Childress’s debut full-length poetry collection, Outside the Frame, pictures a ruby-ripe pomegranate and its roe-like seeds spooned from the mother fruit. Historically, pomegranates are heavy with symbolism and myth: fertility/marriage and childbirth, death/resurrection, mother/daughter attachment and divide, to name a few. These are the seeds that Persephone ate after Hades abducted her to the Underworld, an act that kept her apart from her grieving mother, Demeter, causing winter’s fallow bleakness over the Earth, then being released into spring’s green flourish, only to return below every fall. An explanation of our seasons, with Greek mythology’s typical abduction scene, but also depicting the seasons of a woman’s life—from a girl’s innocence and curiosity to a woman’s fullness of experience and all the chapters of joy, discovery, and hard knowledge in between.

What we glimpse both inside and outside the frame in Childress’s work is a powerful blossoming of women, flesh and mythical, into fervent voice and defiant independence. Mirroring the constrained Persephone’s time apart from light and maternal comfort, Childress’s speakers are wife/mother/homemaker, adolescent, adult, and the biblical women many of us know well from Sunday school days—all straining at the reins of male control and societal convention.

The opening poem, “Putting Up Corn,” perhaps Childress’s signature piece, sets the stage with the Corn Mother’s partner presenting her with a bushel bag of sweet corn for “shucking, silking, washing, cutting, cooking …” She knows wryly that the man, at least for eight hours of labor “in a kitchen where I don’t belong,” has “delivered [her] submission.” Each ear gleaned in her hand becomes a “rosary said to the blessed mother / whose purity he thinks I lack.” The poem’s turn is an italicized prayer combining Protestant, Catholic, and pagan traditions, with a wink to the poet’s surprising humor in trying times: “Hail Holy Queen, I called for takeout again.” Indeed, this poem, like many others, reads like liturgy in common speech, with most stanzas here beginning in the confessional voice: I peel, I strip, I cut, I place, along with certain repetitions that echo incantation: “hard winter which might not come, / hungry children who would.”

The speaker’s father . . . holds a godlike place in her life, baptizing

the faithful and the lapsed alike in the Elk River. With his “King James /high in the air,” his children paid attention, paid respect to a man

who could wash earthly sins away in the “swirling, saving water.”

Poet, playwright, essayist, and editor, Linda Parsons is the poetry editor for Madville Publishing and the copy editor for Chapter 16, the literary website of Humanities Tennessee. She is published in such journals as The Georgia Review, Iowa Review, Prairie Schooner, Southern Poetry Review, Terrain, The Chattahoochee Review, Baltimore Review, Shenandoah, and American Life in Poetry. Her sixth collection, Valediction, contains poems and prose. Five of her plays have been produced by Flying Anvil Theatre in Knoxville, Tennessee.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________