Book Review

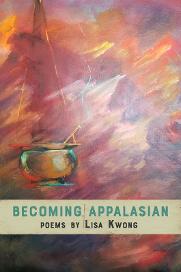

Opening “suspended between shores,” and closing with the question, “when will anything ever be enough?”, Lisa Kwong’s debut Becoming AppalAsian is a poetic feast, counterpoint, and crucial addition to the table of Appalachian literature. Across thirty pages of poems, Kwong meditates on family, identity, and belonging, unafraid to confront the racism and sizeism experienced by her speaker and their Appalachian Chinese family. Sometimes, a chapbook can skim along the surface, leaving the reader intrigued but not quite satisfied—but Becoming AppalAsian is a lush table stacked with plates filled high. Kwong’s collection holds worlds and generations, making her book a strong fit for reading circles, book clubs, community conversations, literature courses, and creative writing courses on Appalachian literature, Asian American literature, Chinese American literature, working-class literature, literatures of immigration and migration, narrative poetics, and more.

Becoming AppalAsian opens with the immigration of the speaker’s parents from Tai Shan, Canton to Radford, Virginia, where Kwong was born and raised and where her (and her speaker’s) parents operated Canton Restaurant. Following several poignant poems of childhood, the speaker comes of age, traveling to college and to China, and returning to the United States “in the time of swine flu” and racism in the expressive five-section center poem “The ABC (Appalachian-Born Chinese) Sequence." Toward the close of the collection, the speaker gains the courage to claim her identity as AppalAsian, relocating to the “Midwest / college town” of Bloomington, Indiana, finding home there but always knowing: “Nothing compares to Mom and Dad’s wontons," and all the complicated love and belonging offered alongside.

Becoming AppalAsian opens with poems to familial ancestors, including the stunning first poem, “On the 42nd Anniversary of My Father’s Swim from China, 10/17/2015," where readers, like the speaker’s father, “watch your friends / tire, disappear beneath bluish-black shores, never / to resurface.” Kwong’s enjambments mirror the visceral swerve from hope to despair, and back again, experienced over this father’s hours-long swim in shark-filled waters and a “love spanning generations of blood.” In her second poem, “Poem for My Mother Who Dared Beyond Tai Shan," Kwong recounts this mother’s years of waiting after her husband’s swim to Hong Kong and their eventual reunion in “America, / the place they call Gold Mountain,” where they start to build “a home / where there will always be enough to eat.” The speaker enters poems as a child soon after, as in the compelling “The Baby Behind the Cash Register at Canton Restaurant,” “Blind Spot,” and “Tai Shan, Canton Came to Radford, Virginia,” embedded in a community of relatives (like her Ngin Ngin, who shares family histories) and place—filled both with moments of belonging and with complex frictions.

Just as her father was “suspended between shores” in the opening poem, the speaker also finds herself having to “carry the bridge between China and America,” as someone both “never fully Chinese” and “never fully American.” When “y’all is home, not ni hao,” she is always trying to “take different worlds and fuse them into a kaleidoscope universe no one has ever seen” even as she knows, in another haunting linebreak that holds several meanings at once, “There is always desire to be / someone else, everywhere else.” Yet, Kwong’s speaker persists in this vital effort to make home in Appalachia, bringing a poet’s sensitivity to the languages and spaces she moves between and inhabits. Literary ancestors, including Frank X Walker, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, and Jean Kwok, offer her the predominantly English-language balm of “words […] // like favorite Bible verses,” even as, at other times: "Cursing in English / only makes me feel worse, / as if I’ve bitten off Lego heads." Moving between worlds of language and community, Kwong continually returns to Appalachian place to ground her speaker’s journeys toward belonging and connection.

Yet, Kwong complicates any easy binary of belonging. The speaker and her sister flinch in their grandmother’s garden from the insults of white men driving by, who shouted “like they were hurling / butter knives at our heads,” and from the laughter and indecent exposure of white boys at Canton Restaurant and a neighboring house. At the same time, however, Kwong also shows how her speaker’s lack of fluency in Mandarin leaves fluent speakers laughing at her like “a storm of fortune cookies / cracking,” as the language “sails over my head / like fish eyeballs.” For her parents, she knows, “English / was a diamond locked in a glass case,” and she herself is “the American diamond daughter.” Yet, the speaker is immersed in shifting environments, as when a cordial waiting-room conversation with a woman about the weather shifts, after the speaker and her mother move into their Tai Shan dialect: “in ten seconds, / your smile morphed / into an axe,” the sudden hostility leaving the speaker almost voiceless.

What does it mean to find home? What would home, for this speaker, look like? As Becoming AppalAsian moves into its final poems, Kwong avoids any simple act of closure.

I used to believe the rumors of who I was.The smell of ripened bananas. A clumsy kite.An elephant running into trees and beehives.

Today I am a songpunctuating the skylike a mermaid’s tail.

I ponder the mirror,study the woman before me,see the tear-stained tub of lard,see the runner’s legs,see the glittering, Cinderellablue earring heart.

Lucien Darjeun Meadows was born and raised in what is now sometimes called Virginia and West Virginia to a family of English, German, and Cherokee descent. A past contributor to Still: The Journal, Lucien has received fellowships and awards from the Academy of American Poets, American Alliance of Museums, and National Association for Interpretation. His debut poetry collection, In the Hands of the River, was published by Hub City Press in September 2022.

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Masthead Submit

_____________________________________________