Book Review

Listen to Bob Marley: Novellas and Stories

~

But Still the Land Sings

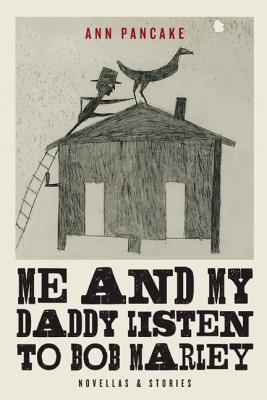

Power of place is at the heart of Ann Pancake’s second collection of stories, Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley. In two novellas and nine short stories, Pancake explores worlds of characters who are connected to their homes in ways that at once harm, haunt, and heal them. With sharp and unflinching prose, Pancake represents Appalachia, and the universal human heart, in all its beautiful and brutal complexities.

The range of narrators represented in these stories is extraordinary. The opening novella, “In Such Light,” is a coming of age story about Janie, a teenage girl who befriends her mentally handicapped uncle during a summer spent at her grandparents’ house in Remington, West Virginia. Despite having dreams for the future, Janie allows herself to become “run down” at college and fills herself with doubt that if even if she succeeds at school, she will wind up back in her hometown in McCloud County, where “grandeur was found only in nature, and the palatial and luxurious not at all.” The novella is a slow boil, detailing evenings Janie spends drinking with Uncle Bobby, taking turns telling familiar stories. We follow Janie through a tumultuous summer fling with neighbor Nathan. We are with Janie through dangerous rides on the back of Nathan’s motorcycle and as she works her shifts as a popcorn girl at the Alexander Henry movie theater. We are reminded throughout of the way Janie saw the world, and Remington, when she was a child. It is in the end, when Janie sees her reflection in a mirror of an abandoned dressing room at the theater, that Janie, and the reader, see the changes she is discovering about herself and her world.

Janie isn’t the only youthful narrator in the collection. Several of Pancakes stories are written from the perspective of children and adolescents and serve as gut wrenching reminders of the levels of pain that come with discovering the world around us. “Mouseskull” is the first-person story of Lainey, a fourth grader who struggles to balance life in elementary school with life at home, where her grandfather’s recent suicide haunts her family. Lainey is afraid of her grandfather’s ghost, but fascinated by stories about him. When she stumbles upon the skull of a mouse in the barn, it becomes her morbid talisman that she wears around her neck and at night perches atop her Living Word Children’s Bible; it is her constant reminder that death is all around her. In Lainey’s world, a world where her classmates are “desensitized to the unusual,” children are wise beyond their years and often observe the world with more foresight and maturity than the adults among them.

. . . it seems far-fetched that a toddler can so accurately describe his world, but Pancake erases all doubt as she showcases the struggle Mish has between understanding his drug-addicted father’s wrong doings and articulating them.

Pancake’s masterful command of language is what makes her child narrators believable and full of life. In “Mouseskull,” Lainey describes her world with a series of invented phrases, often using hyphenated words like “scripture-trapped” and “dinner-smelled-bewitched” to describe her place in the grown-up world around her. Similarly, in the title story, “Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley,” it is three-year-old Mish’s language that separates him from his adults. As the story opens, it seems far-fetched that a toddler can so accurately describe his world, but Pancake erases all doubt as she showcases the struggle Mish has between understanding his drug-addicted father’s wrong doings and articulating them. We believe Mish’s observations as he sees “the man inside” his daddy that totes the toddler to parties, promising reggae music along the ride that reminds Mish of better times. The fact that Mish’s daddy is the only one who can understand his youthful speech impediment is the one thing that keeps Mish from telling the other adults in his life about the nights he spends sleeping in strangers’ beds as his father parties in rooms beyond. In the end, Mish practices his words, his only defense against the brutal grown-up world where drugs have taken his father’s teeth, his dignity, and Mish’s treasured Dallas Cowboy coat. In the end, it feels natural that “Mouseskull” and “Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley” should be narrated by children, as Lainey and Mish are perhaps the most relatable narrators in the collection, reminding us that even as adults, the pain and confusion of suicide and drug addiction are nearly impossible to understand.

In the middle of Pancake’s compelling characters, the most haunting is Appalachia herself. In her 2007 novel, Strange as This Weather Has Been, Pancake told an unforgettable story of the damages of mountain-top removal mining on the land and people of West Virginia. Many of these stories are also set in West Virginia, and the landscape of Pancake’s native state is as alive as any of her narrators.

In “The Following,” the main character lives in Seattle, but is called back to her childhood home of West Virginia by an unearthly “knowing” that leads her to animal bones. More than just the urge to follow the “knowing,” the actual land of Appalachia pulls at this character. She says she had “grown up roaming Appalachian hills and needed wild like a nutrient even as an adult.” This attachment to the land, this need to be one with Appalachia even with all its industry-induced devastation, is at the core of all of Pancake’s characters.

It is in the penultimate story, the shortest and perhaps the most dynamic of the collection, that Pancake brings all the issues of land, loss, and healing together. “Sab,” is narrated by a middle-aged woman whose cousin has come home to Appalachia after many years of being away. Sull left her hometown as a young woman, and her fate away from the hills has been speculated and rumored since her departure. Those she left behind, including her cousin, spun wild tales of Sull’s money and drugs and ruin, and when she returns to her cousin’s house, she gives no details of her history. She spends all day roaming the hills near her cousin’s house in an attempt to “get the city out” of her.

The narrator has had her share of losses – her son turned to drugs, her husband gone, a fight with breast cancer. She watches her cousin search for herself in the hills she never left and reminisces about their times together as children, rubbing salve they called “sab” on the family horse to heal his wounds. It is in this story that Pancake shows us that despite the bleak reality that surrounds many of her characters and their homeland, there is still hope at the center of their narratives. The narrator asks,

“And how much can life take from you? Sull, your livelihood, lovers, beauty, reputation, dignity. Me, my son, husband, breasts, innocence, righteousness, security. And I’m not an ignorant woman. The whole world, I know, is losing, too. Rivers drying, mountains toppling, cities drowning under storms, and not many miles from here in woods like these, they are even shattering the underground.

But still, the land sings. And not just a singing, but louder, stronger, I tell you, every month it gets easier to hear. Because – listen – when everything is losing, everything is lightening, the distance between us thins and sheds. This is what loss gives. In these delicate, sharp, and beautiful, these brilliant unraveling days.”

It is not accurate to describe Appalachia as a place of romanticized rolling hills or as a gritty black hole of drug deals and crime. In truth, Appalachia is many-tiered. Often writers fail to accurately portray the nuances of the region and its people. Pancake does not. In Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley, Pancake represents Appalachia in all its complexities – the beauty, loss, environmental travesties, and, for those who stay as often as for those who leave, the sab to heal what’s broken.

~

Amanda Jo Runyon is a mother, writer, and instructor in Pike County, Kentucky. Her fiction and poetry have appeared in journals such as The Louisville Review, Pine Mountain Sand & Gravel, and Kudzu, as well as Seeking Its Own Level, volume 4 of the Motif anthology series. She is co-editor of the literary journal The Pikeville Review.

~

_____________________________________________

Home Archives Fiction Poetry Creative Nonfiction Interview

Featured Artist Reviews Multimedia Contest Masthead Submit Feedback

_____________________________________________